Nowadays it seems the federal government’s intent on making owning and operating a business more difficult than ever.

And employers in Nevada are noticing the difference.

“It’s just a mess,” says one experienced business leader from Northern Nevada.

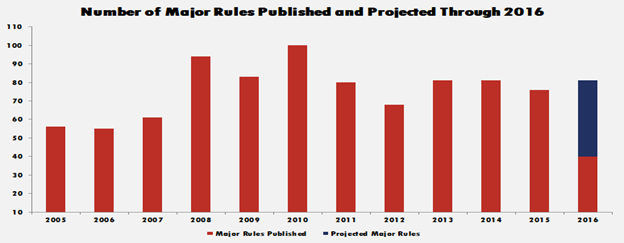

Updates to the Fair Labor Standards Act (“FLSA”) — changing rules when employers must pay overtime wages — are only the most recent in hundreds of regulations added by executive agencies during Obama’s presidency.

Time and again, the Obama White House has sought implementation of thousands of pages of restrictive regulations that have effectively reduced — by billions — the nation’s gross domestic product.

In April, Nevada Journal’s Steven Miller highlighted the major hassle associated with the new updates to federal labor regulations. (See “Are you one of the millions of employees who Obama wants punching time-clocks?”)

In April, Nevada Journal’s Steven Miller highlighted the major hassle associated with the new updates to federal labor regulations. (See “Are you one of the millions of employees who Obama wants punching time-clocks?”)

At the time, the proposed rules were still being finalized. Now, several months after the final text has been published and assigned an implementation date — December 1, 2016 — human-resources administrators are faced with updating their organizations’ employee policies to reflect the federal-rule changes.

Moreover, they must try to do so without compromising their organizations’ existing functionality.

At issue, specifically, is the Department of Labor’s raising of the minimum-salary threshold that allows white-collar employees to be exempt from overtime rules.

Under the rule being replaced, full-time salaried workers earning over $23,660 annually who also meet one of the white-collar duties tests are exempt from FLSA overtime mandates. To be considered white-collar, an employee must work in an executive, administrative or professional capacity, as described by the Department’s Wage and Hour Division.

Such guidelines are notoriously subjective and have frequently occasioned back-pay legal actions against employers charged with misclassifying their workers, intentionally or not.

The advantages of managing salaried workers are clear — notably, the flexibility of scheduling unconstrained by requirements that employees must “clock-in” to account for every minute at the workplace.

Under the feds’ new rule, the required salary level for white-collar exempt status more than doubles, to $47,476. The Department of Labor argues that 4.2 million additional workers will benefit from the new rule — through either new DOL overtime protections or through the new rule’s implicit pressures on employers to hike salaries above the new salary threshold.

Most employees who now find themselves below the threshold salary will probably be reclassified as hourly workers. Human-relations staff will now be compelled to monitor those workers’ hours so that they do not exceed 40 hours per week. Otherwise, their organizations must, under the rules, pay overtime wages.

In this sense, the law itself hasn’t necessarily become more complex. Instead, the same practices required by the old law will now apply to a substantially greater number of employees nationwide, forcing businesses into dramatic action to comply.

Whatever the proper semantics may be, the change guarantees thousands of hours’ worth of administrative duties will be undertaken by Nevada firms to achieve compliance.

Just ask Dena Higgins, SPHR, HR manager for Baldini’s Casino, in Sparks. She has first-hand knowledge of the new pressures on businesses from the Obama administration’s new FLSA rules.

“It’s just a mess,” she says. “The new rules have forced an extreme adjustment to our HR policies and practices.”

Wiggins estimates that she’s already spent hundreds of hours preparing for when the new rules take effect. Among the 220 or so employees she oversees, about 25 of them will be directly affected.

“Right away, we needed to decide whether to simply boost their salaries to the threshold point, a move which would ease the administrative burden of the changes,” notes Wiggins.

Unfortunately, the costs of doing so would raise personnel costs by at least $300,000 per year. So “that really isn’t a realistic option,” she claimed. The result is that department heads must now keep tabs on every hour worked by those more than two dozen affected employees.

Teresa Finn, HR director for Server Technology, Inc. in Reno, has had a relatively-easier time navigating the new rules. A big reason is that she began learning of the impending changes over a year ago.

Apart from her full-time job, Finn is president of the Northern Nevada Human Resources Association. Thus, since learning of the proposed updates, she has been planning accordingly.

Finn estimates that only 12 of the employees for whom she is responsible at Server Technology will be directly affected.

Still, she finds irony in that the government seems the only proponent for the change — and not her employees.

“Our employees think this is nonsense. They’re all happy, nobody has issues with how they’re currently being paid,” Finn offers.

“They ask me, ‘Do we have to make the change?’ And I tell them ‘Yes, because it’s the law,’ and we would face huge fines otherwise.”

While acknowledging that the “old” minimum salary threshold may be outdated, Finn expresses frustration that the Department of Labor chose not to clarify other confusing aspects of the current law.

“If the [Department] really wanted to simplify these rules, it should’ve started with redrafting the worker classifications.”

Here, Finn refers to the so-called ‘white-collar duties tests,’ which are glaringly vague. To gain exempt status, an employee must satisfy one of the tests — professional, administrative, executive, outside sales, or IT — while also earning at least the threshold salary.

Finn highlights the ambiguity in the tests — such as the description of responsibilities required to gain ‘professional’ exempt status. Beyond earning at least the threshold salary,

a) The employee’s primary duty must be the performance of work requiring advanced knowledge, defined as work which is predominantly intellectual in character and which includes work requiring the consistent exercise of discretion and judgment;

b) The advanced knowledge must be in a field of science or learning; and

c) The advanced knowledge must be customarily acquired by a prolonged course of specialized intellectual instruction.[1]

Due to this uncertainty in how to properly classify a worker, Finn suggests “there is probably not a single organization in the country which fully complies with the law in every sense. It’s too vague — the government can always argue something differently after the fact.”

Baldini’s Wiggins identifies another challenge the new changes pose for employers: Employees perceiving the new requirement that they clock in as a demotion of sorts.

“One of the challenges has been to convince the employees that switching from ‘salaried’ to ‘hourly’ compensation is not a downgrade,” says Wiggins. “It just necessarily reflects changes to the law.”

As a show of good faith and support to her employees, Wiggins plans to have all employees clock-in daily — even the salaried employees — so as not to single-out the newly-classified hourly workers.

Not only do the new rules produce mass organizational confusion, she indicates, but all the extra administrative time they require forces the firm to shift focus away from other, more salient personnel matters.

“Recruitment was already an issue for us,” says Wiggins, “because we start at minimum wage. Now, because we’ve been spending so much time getting ready for December [when the changes take effect] we have even less time to spend towards recruiting efforts.”

Apart from being a sizeable inconvenience, the new rules also come at a precarious time for the national economy: Since 2013 the labor force participation rate has been hovering under 63 percent[2].

Prior to that, no calendar year had ended with a sub-63 percent labor force participation rate since 1977[3]. (Nevada’s rate mimics the national rate at 62.9 percent, according to a recent analysis by the Nevada Policy Research Institute.)

Accordingly, critics wonder why the new rule — which they say will deter new hiring, generally — is being implemented in lieu of one that promotes hiring.

The Department of Labor advertises on its website that the purpose of the updates is “…to simplify and modernize the rules so they’re easier for workers and businesses to understand and apply.”[4]

However, the experiences of HR professionals across the state tell an altogether different story.

Daniel Honchariw, MPA, is a public policy analyst at the Nevada Policy Research Institute. He received his bachelors from Cornell University’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations.