LAS VEGAS — The Lake Tahoe Basin — its residents are ceaselessly told — has suffered much environmental damage over the decades.

Rarely mentioned, however, is a remarkable fact: Much of the damage has actually been at the hands of the lake’s ostensible protectors.

While this reality is only occasionally acknowledged, it’s a critical part of basin history and needs to be known if the Tahoe environment is to flourish.

Take, for example, Lake Tahoe’s famed blue waters, their central importance to the basin, both economically and aesthetically — and the serious threat posed by those waters’ decades-long diminishing clarity.

That threat makes entirely believable the explanation that the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency has repeatedly advanced for the necessity of the 2012 Lake Tahoe Regional Plan Update.

As recently as Feb. 11, 2013, TRPA Director Joann Marchetta offered it in a news release. Responding to the latest Sierra Club lawsuit against the agency, she said:

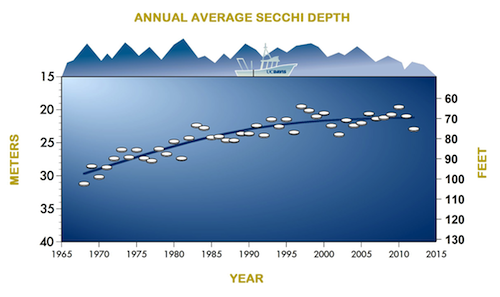

Lake Tahoe’s health continues to be threatened by pollution from aging development… The framework created with the 1987 Regional Plan was focused on stopping runaway development and controlling the impacts of new construction. The strict rules were successful, but most development in the watershed pre-dates the 1987 plan. Neighborhoods and aging town centers continue to feed pollutants like fine sediment, phosphorus and nitrogen into Lake Tahoe, reducing the Lake’s famed clarity from 100 feet measured in the 1960s to an average of around 70 feet today.

This was no one-off statement. The TRPA director had also sounded the same note two years ago, during the 2011 Nevada Legislature:

The TRPA discovered in the late 1990s that acting only as a regulatory agency does not improve the lake or the environment of Tahoe, especially with fewer and fewer resources available to enforce complicated regulatory schemes. And we know now that doing nothing will not improve the lake or its environment, and in fact will lead to the continued degradation of the lake and our communities….

We can reclaim the famed clear blue waters of Lake Tahoe, while reducing the nearly 20 percent unemployment rate in our communities, not by building but by rebuilding. (Emphasis in the original.)

Implicit within these statements is a clear admission that the bi-state regimen of control imposed on the basin for over four decades left in place for most of that time the most concentrated sources of the lake’s clarity problem.

Yet it was that clarity issue — ballyhooed repeatedly throughout the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s and still today — that was primarily advanced to justify the Tahoe Compact’s controls.

So: If the issue was so important, why has it taken so long, practically speaking, for something to be accomplished on that front?

Marchetta’s account suggests one possible answer: that the 1987 TRPA Regional Plan essentially handcuffed regulators, preventing them from establishing effective incentive programs that would lead owners to upgrade their aging, offending properties.

Another possible answer — constant lawsuits from militant environmentalist organizations — gets to the same apparent root cause: A widespread, simplistic notion that any development in the basin must be bad is easily politicized, thus adding fear to the normal human component of indifference in politicians, appointees and bureaucrats.

Four-plus decades, however, still seems a very long time for the central problem of lake clarity to have always ended up on the sidelines.

It has never been a secret, after all, that, to stop the Tahoe basin’s 1950s and ’60s-era properties from continuing to cloud the lake’s water, those properties needed rebuilding.

Thus, long before the 1987 plan referenced by Marchetta — and even before the 1980 revisions to the California-Nevada bi-state Tahoe Compact imposed new restrictions on lake property owners — opponents of new restrictions were pointing out that, as proposed, the new rules would only ensure continuing environmental damage for the lake.

Illuminating evidence exists within the historical archive of TRPA legislation maintained online by the Nevada Legislative Counsel Bureau.

In 1979, the governors of California and Nevada — a young Jerry Brown and the late Mike O’Callaghan — were both harkening to environmentalist demands for more legal barriers to building at Lake Tahoe.

During the preceding decade, the League to Save Lake Tahoe and the Sierra Club had allied with different agencies of the State of California in multiple lawsuits that sought to legally define building, per se, as Tahoe’s problem, and also to have pre-existing Nevada gaming at the lake declared a common-law nuisance.

After suffering multiple defeats in federal court — “the 1969 Compact is not the powerful antigrowth measure that some people would wish it to be,” said the Ninth Circuit, more than once — the League and the California agencies settled on a solution: Change the bi-state compact.

Legislation to do just that took form in the consultations between Brown and Callaghan, and, during the 1979 Nevada Legislature, in Assembly Bill 503.

However, that bill’s basic premise — that construction, per se, was the basin’s problem — was challenged. Critics of the building restrictions already in place under the then-existing 1968 version of the bi-state compact, argued that construction restrictions were actually contributing to the continuing degradation of the lake’s water clarity.

The LCB’s compiled legislative history for AB 503 contains — badly reproduced — a copy of a mimeographed two-page flyer circulated at the lake by “The Council for Logic” and given to lawmakers during the 1979 session.

“So now we have regional government (appointed, not elected) instead of regional planning,” complain the South Lake Tahoe authors of the flyer. “What has it done for us? Prevented rebuilding of older blighted areas that down-grade our community either because of arbitrary land coverage restrictions or massive down-zoning.” (Emphasis added.)

Of course, the “Council for Logic” and others who shared its outlook were shouting into the wind. Official opinion within the California and Nevada political classes was — as always — quite confident of itself.

Then, as subsequent decades passed, and lake clarity continued declining, even establishment authorities began realizing that the TRPA policeman role was not actually addressing the problem for which the agency ostensibly had been established.

“[M]any basin actors,” argued a Fall 2003 article in the Natural Resources Journal, had by 1997 become convinced “that a continued emphasis on stringent land use regulations was unlikely to reverse declining water clarity and that a greater emphasis on nonregulatory approaches” — such as habitat restoration and altering developed properties to mimic the water-filtering character of Tahoe’s undeveloped watershed — was needed.

“In part, this shift in focus from regulatory to nonregulatory solutions,” wrote authors Mark Imperial and Derek Kauneckis, “was due to the disappointing results of the first two threshold reviews,” released in 1991 and 1996, of progress toward accomplishing the goals of the 1987 general plan.

“The reviews suggested that regulations alone would not improve Lake Tahoe’s water quality since many of the current environmental problems existed due to development and poor land use planning decisions during the past few decades.”

So Marchetta’s argument — that TRPA has little chance of reclaiming “the famed clear blue waters of Lake Tahoe” unless property owners have better incentives for upgrading old basin properties — has much support from the basin’s history.

Presumably that is why both the League to Save Lake Tahoe and the Nevada Conservation League participated actively in the negotiations leading to the TRPA-approved 2012 Regional Plan Update — and then declined to join the lawsuit launched by the Sierra Club and Friends of the West Shore against that new version of the Regional Plan.

“It’s certainly true that some existing development is polluting the lake,” said Kyle Davis, conservation league political and policy director. “It’s an open question as to whether provisions of the 1987 plan were preventing redevelopment or whether it was due to factors outside of our control (nationwide and global recessions, changing consumer preferences, etc.).

“At any rate, it was clear to us that the pace of redevelopment needed to be quickened to try and combat these pollution concerns. As a result, we have attempted to include more incentives for redevelopment in the new Regional Plan. These include increased benefits (additional tourist accommodation units, additional square footage) for transferring development out of environmentally sensitive areas.”

Notably, the Sierra Club lawsuit only demands even tighter controls on lake residents and argues that the incentives offered within the Regional Plan Update are doomed to fail.

However, the most recent Tahoe clarity readings by TERC — the Tahoe Environmental Research Center at the University of California, Davis campus — are, for supporters of TRPA, encouraging.

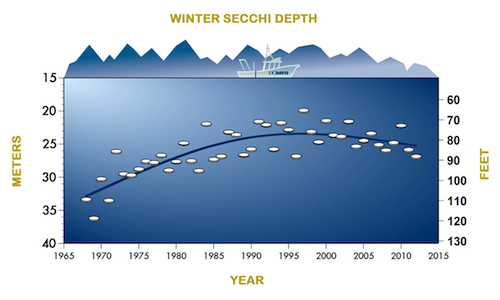

Winter readings for 2012 were reported to have improved for the second year in a row, bringing the annual “average” reading down by 6.4 feet, to 75.3 of visibility.

“The improvement we see in both the summer and winter clarity during 2012 is very encouraging,” said Geoffrey Schladow, TERC director.

“The improvement we see in both the summer and winter clarity during 2012 is very encouraging,” said Geoffrey Schladow, TERC director.

While Tahoe “will continue to be subjected to a range of disturbances, each of which has the potential to impact clarity,” he said, there is a “growing belief that managing for clarity is possible.”

Does TRPA’s new appreciation for incentives get the credit for the last two years’ reported improvement in lake clarity?

Apparently so.

“Redevelopment had been occurring before” the new Regional Plan Update, says League to Save Lake Tahoe Communications Liaison Amanda Royal, but “those projects required the TRPA board to approve the exceptions to the code.”

“Redevelopment had been occurring before” the new Regional Plan Update, says League to Save Lake Tahoe Communications Liaison Amanda Royal, but “those projects required the TRPA board to approve the exceptions to the code.”

The 2012 version of the regional plan, she says, “codified some of the incentives that were already being used for redevelopment, in order to streamline the process.

“One could say that the real impediment to redevelopment was financial,” she told Nevada Journal. “It simply was not financially beneficial to, for example, buy a 1950s one-story motel in South Lake Tahoe and replace it with a one-story motel with as many rooms, but more open space.

“Less pavement and more open space are the key to allowing rain and snowmelt to seep into the ground, where pollutants like sediment are naturally filtered out. So allowing more height and density, for example, might allow an investor to buy two motels that are side by side, rebuild higher with the same number of rooms on the same footprint as one motel, while creating open space on the second lot.”

Royal noted that an emboldened TRPA governing board had utilized that same concept in the 1990s to allow construction in South Lake Tahoe of a six-story hotel, where technically a two-story limit was in place. In exchange, she said, “Old motels were torn down and turned into artificial wetlands.”

Nevada Journal repeatedly contacted TRPA on this story but received no response by deadline.

The Tahoe lake-clarity issue is not the only instance where Tahoe basin residents have suffered significantly from the always-volatile mix of government power and environmentalist zealotry.

Other instances include the 2007 Angora fire, the federal MTBE mandate and the federal ethanol mandate.

Steven Miller is the managing editor of Nevada Journal, a publication of the Nevada Policy Research Institute. For more in-depth reporting, visit https://nevadajournal.com/ and http://npri.org/.

Read more: