Lizhong Fan’s desk was among a crowd of cubicles at the Arizona Counter Terrorism Information Center in Phoenix. For five months in 2007, the Chinese national and computer programmer opened his laptop and enjoyed access to a wide range of sensitive information, including the Arizona driver’s license database, other law enforcement databases, and potentially a roster of intelligence analysts and investigators.

The facility had been set up by state and local authorities in the aftermath of the 9/11 terror attacks, and so, out of concerns about security, Fan had been assigned a team of minders to watch him nearly every moment inside the center. Fan, hired as a contract employee specializing in facial recognition technology, was even accompanied to the bathroom.

The facility had been set up by state and local authorities in the aftermath of the 9/11 terror attacks, and so, out of concerns about security, Fan had been assigned a team of minders to watch him nearly every moment inside the center. Fan, hired as a contract employee specializing in facial recognition technology, was even accompanied to the bathroom.

However, no one stood in Fan’s way when he packed his equipment one day in early June 2007, then returned home to Beijing.

There’s a lot that remains mysterious about Fan’s brief tenure as a computer programmer at the Arizona counterterrorism center. No one has explained why Arizona law enforcement officials gave a Chinese national access to such protected information. Nor has anyone said whether Fan copied any of the potentially sensitive materials he had access to.

But the people responsible for hiring Fan say one thing is clear: The privacy of as many as 5 million Arizona residents and other citizens has been exposed. Fan, they said, was authorized to use the state’s driver’s license database as part of his work on a facial recognition technology. He often took that material home, and they fear he took it back to China.

Under Arizona law, then-Gov. Janet Napolitano and Maricopa County Sheriff Joe Arpaio, whose agencies admitted Fan into the intelligence center, were required to disclose to the public any “unauthorized acquisition and access to unencrypted or unredacted computerized data” that includes names and other personal information.

To this day, they have not.

Terry Goddard, attorney general of Arizona in 2007, said Fan’s access and disappearance should have been reported to his office, but it was not. Arizona law puts the attorney general in charge of enforcing disclosure.

The state was supposed to have scrubbed drivers’ names and addresses from the license data. State officials denied requests to discuss the extent of the data breach, including what personal information was in the files.

In fact, a review of records shows that David Hendershott, who was second-in-command at the sheriff’s office, moved aggressively to maintain silence, a silence that has now lasted some seven years. Two weeks after Fan departed, Hendershott directed others in writing not to discuss Fan and the possible breach. In an email to the outside contractor that had hired Fan, Hendershott wrote: “Keep this between us and only us.”

In fact, a review of records shows that David Hendershott, who was second-in-command at the sheriff’s office, moved aggressively to maintain silence, a silence that has now lasted some seven years. Two weeks after Fan departed, Hendershott directed others in writing not to discuss Fan and the possible breach. In an email to the outside contractor that had hired Fan, Hendershott wrote: “Keep this between us and only us.”

Even among administrators at the Phoenix center, very few learned that the Chinese programmer had left the country or that their own personal information might have traveled with him. Mikel Longman, the former criminal investigations chief at the Arizona Department of Public Safety, said he received no warning about the incident.

“That really is outrageous,” Longman said. “Every Arizona resident who had a driver’s license or state-issued ID card and all that identifying stuff is potentially compromised. That’s a huge breach.”

Napolitano, who went on to serve as President Barack Obama’s secretary of Homeland Security, did not reply to multiple interview requests.

Hendershott, Arpaio’s longtime chief deputy, hung up on a reporter when reached by telephone. The sheriff’s office fired Hendershott in 2011 over an array of alleged misconduct. And he in turn filed suit in 2012, saying his legitimate law enforcement work had been mischaracterized as abuses of power. His suit was dismissed earlier this year. Today, he sells real estate in west Phoenix.

Col. Robert Halliday, the director of the Arizona Department of Public Safety who formally oversaw the operations of the intelligence center at the time Fan worked there, also did not respond to repeated interview requests.

Current officials with a handful of agencies involved with the intelligence center offered a variety of reasons for declining to answer questions about Fan and the possible breach.

The public safety agency initially denied that any potential breach had happened, then said the matter was the subject of a confidential FBI investigation. Later still, the department argued the case was a personnel matter, and thus the agency would not comment as a matter of policy. The sheriff’s office said that during the time that Hendershott was still working for the agency, he never reported anything about Fan – his hiring, his work or his flight.

Seven years after the potential breach, then, it is still unclear how closely law enforcement looked into the incident or what steps, if any, it took as a result. The FBI opened a probe shortly after Fan’s disappearance, according to records and a former federal investigator, but the bureau has never made its findings public.

Perryn Collier, spokesman for the FBI’s Phoenix office, said the bureau won’t comment on investigations involving Fan.

Chinese espionage has made news in recent months as federal investigators have revealed successful assaults by hackers against businesses and government. Last March, homeland security officials in Washington discovered that cyber attackers later traced to China had accessed data on federal workers who’ve applied for top-secret clearance. These electronic break-ins were conducted remotely, continents away from the servers holding the data.

How the Phoenix intelligence center found itself vulnerable to a serious security breach, however, was neither much of a technological feat nor, it seems, the result of masterful espionage. Indeed, an investigation by The Center for Investigative Reporting and ProPublica – built on more than 50 interviews and the examination of thousands of pages of federal investigative reports, criminal and civil court filings, internal correspondence and immigration records – shows the episode at the intelligence center came off rather easily.

John Lewis arrived as the FBI’s special agent in charge of the Phoenix division in the spring of 2006. Lewis, now director of security for the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in the San Francisco Bay Area, had a vague recollection of a contractor or subcontractor working at the center. But he said he did not specifically recall that the person was a foreign national, nor did he have any “immediate recollection” of a security breach.

“No one ever sat in my office and asked about having a foreign national inside the fusion center. That’s nuts,” Lewis said, adding that if he had been asked, his response would have been, “Can we do a little bit better guys?”

The chance that Fan made off with a raft of sensitive material was made possible by a set of cozy relationships – among a tainted sheriff’s official, a dubious technology startup company and a woman who U.S. government officials think is a Chinese spy.

That really is outrageous. Every Arizona resident who had a driver’s license or state-issued ID card and all that identifying stuff is potentially compromised.

Mikel Longman

Intelligence center employees are supposed to hold a “secret,” or midlevel, security clearance, based on a background investigation completed most often by the federal Office of Personnel Management. Aside from cursory background checks as part of his visa application, it’s unclear if Fan underwent deeper probing. The company that hired him also received little to no extra scrutiny.

Paul Haney, a former special agent with Immigration and Customs Enforcement who was based at the Phoenix center, said discussion of the possible breach was kept to whispers. That reticence came as much from humiliation as security concerns.

“The whole thing was very embarrassing, what he had access to,” Haney said. “I’m embarrassed for everyone left with their asses hanging out.”

A New Idea to Prevent Terrorism

After the 9/11 hijackers crashed planes into the World Trade Center, the Pentagon and a Pennsylvania field, law enforcement officials decided that local police and federal intelligence agencies should improve how they shared information. The hope was that greater coordination among various levels of law enforcement would increase the chance that future attacks could be avoided.

In Arizona, Norman Beasley, a top executive at the Department of Public Safety, and his friend, Ray Churay, an FBI agent working anti-terror cases, came up with the concept of a physical space where all manner of law enforcement agencies could work side by side. The U.S. intelligence community was initially skeptical that local police had much to offer.

“We did not get a lot of support from the beltway, because we were some old country boys from out here in Arizona,” Beasley said.

But Napolitano, as governor, personally lobbied for federal dollars and FBI involvement, and in October 2004, the state opened its intelligence facility, one of the first “fusion centers” in the country.

The center won early praise for how smoothly it distributed raw intelligence across agencies. The Washington Post described Phoenix’s operation in 2006 as “one of the best-run and most effective” intelligence facilities in the U.S.

Arizona’s public safety department runs the center, but more than 20 police agencies statewide deploy some 200 personnel there. The Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office has been involved from the center’s inception, and Arpaio, the legendary anti-immigrant crusader, eventually sought a major role in its operations.

It was Hummingbird Defense Systems, a small Phoenix firm striving to break into the security technology market, that offered the opportunity. Hendershott, Arpaio’s chief deputy, had years before become friends with Steve Greschner, Hummingbird’s chief executive.

In fact, Hendershott first hired Hummingbird in 2003 to use its facial recognition software to watch for sex offenders at a Phoenix elementary school. The sheriff’s office installed it soon after at its outdoor jail, famously known as Tent City. The fact that the technology flopped – one report by jail officials said a day’s growth of a beard defeated its ability to accurately identify prisoners – didn’t deter Arpaio’s office, in the person of Hendershott, from encouraging Napolitano to put Hummingbird’s technology to work at the intelligence center.

A Novel Foray into National Security, With Help from China

Greschner, now 60,acknowledges he was an unlikely candidate to get involved in sensitive law enforcement work before he started Hummingbird. He had worked for Cisco Systems selling servers and other networking equipment to government agencies in and around Phoenix, including the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office.

He was a talented salesman and became a millionaire when Cisco’s share value soared dramatically in the late 1990s, earning $1.4 million the year before he left the company. For the first six months after he quit Cisco, he tried his hand learning to be a cattle-roping cowboy, he said.

After retiring from Cisco in 2000, Greschner poured his money into new ventures. He spent more than $300,000 on a license for software developed by a government scientist for the Sandia National Laboratories and other sensitive sites. The “command-and-control” program makes disparate technologies operate in sync. And when Greschner established Hummingbird Communications in 2001,government records show, his ambitions were limited to selling telecommunications networks.

Greschner said it was the 9/11 terror attacks that stirred his patriotism, and with it a desire to enter the national security business. Technologies capable of identifying people faster and more reliably than the human brain were in great demand but in short supply.

And so he formed a second company called Hummingbird Defense Systems, though internal business records, interviews and correspondence make clear that the firm’s technical capabilitieswere lacking.

The company didn’t employ a single engineer; Hummingbird relied instead on outside contractors to make its products function.

Greschner himself was not a programmer. Before entering the field, Greschner said he “had no idea what a biometric was.”

“He had the razzle-dazzle and used everyone else’s technology,” said Rob Schorr, a former sales executive for another security firm who briefly partnered with Hummingbird on airport checkpoint systems.

Greschner struck deals with other technology companies that had written algorithms to recognize facial features in still images. The software that Hummingbird ultimately used came from a Canadian firm, Acsys Biometrics. Tests by the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology obtained by CIR and ProPublica found that Acsys’ program ranked far behind several competitors.

Hummingbird thus struggled to get government work. One project it later won, to install security equipment at a tiny Nevada airport, ended in litigation when the system didn’t work.

The company had few prospects until late 2002, when Greschner partnered with a man named Gang Chen.

Chen had emigrated from China almost a decade earlier and had a green card. He’d owned an interior design company in Beijing and, in an interview last year, said he had financial backing from Jilin Province Trust, a state-owned investment firm in northern China, to get into the U.S. technology market.

To Greschner, Chen introduced himself as a Chinese businessman looking to sell U.S. security software in China. Chen said he was authorized to distribute technology developed at the China Institute of Atomic Energy internationally.

He proposed a partnership between his company, Detaq Science, and Hummingbird. The deal was sealed when Chen sent his business partner, a tall and strikingly beautiful woman named Xunmei Li, better known as Grace, to meet Greschner.

“Some people call that love at first sight,” Greschner said in an interview. “I’m not going to say it’s that.”

He and Li began dating immediately.

Working with Li and Chen, Hummingbird’s outlook brightened. Li, a now 44-year-old naturalized U.S. citizen raised in Shanghai, turned out to possess impressive ties to Chinese law enforcement.

Working with Li and Chen, Hummingbird’s outlook brightened. Li, a now 44-year-old naturalized U.S. citizen raised in Shanghai, turned out to possess impressive ties to Chinese law enforcement.

Li and Chen soon secured Greschner a meeting with Chinese officials in London, and in time, according to Greschner and others with knowledge of the deal, he sold his fledgling facial recognition program to the Beijing Municipal Public Security Bureau, which installed it in Tiananmen Square.

“Suddenly the doors were opening” for Hummingbird, said David Edger, former associate deputy director for the National Clandestine Service, an arm of the CIA, and a past business partner of Greschner’s.

Greschner connected Hendershott, his benefactor at the sheriff’s office, with his newfound associates in China. In fall 2006, Hendershott took the first of several trips to Beijing with Greschner, Li and Chen.

At the time of that trip, Napolitano had just agreed to have the sheriff’s office facial recognition system deployed at the Phoenix intelligence center. Greschner said he offered to donate his technology, and the sheriff’s office – with no solicitation of other bids – agreed, offering to pay Hummingbird for maintaining the software program over the years. County finance records, obtained by the Electronic Frontier Foundation and shared with reporters, show the sheriff’s office paid Hummingbird roughly $16,000 for fiscal year 2009.

Sheriff’s officials said Hendershott struck the terms of the deal on his own, without the involvement or approval of the office’s procurement officials.

It turned out, though, that Greschner had already ceded significant control over Hummingbird’s inner workings to Detaq, his business partner and liaison to China. In a February 2003 letter to Greschner, Chen stipulated that, going forward, he and Li would get a say in which engineers Hummingbird could hire.

Detaq was responsible for “necessary technology people,” Chen wrote. “You and Detaq will determine who the good candidates are for the installation and tuning of the system.”

Bringing the facial recognition system online at the intelligence center was the most daunting project Hummingbird had undertaken. It would require an expert programmer. Li told Greschner she knew the ideal engineer: Lizhong “Larry” Fan.

A Member of the Club

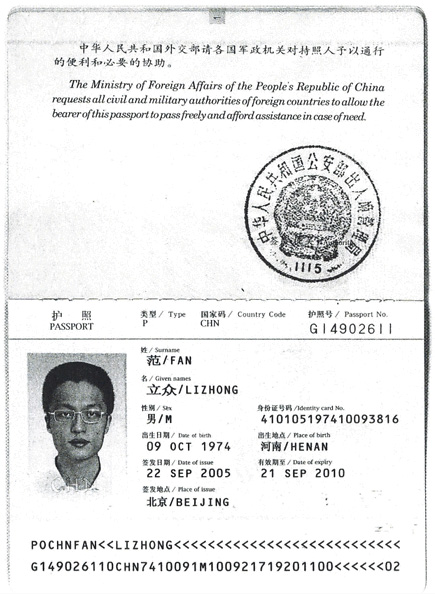

In his Chinese passport photo, Fan appears young enough to be a teenager, with a thin frame and black hair cropped short. He arrived in Phoenix in January 2007, a 32-year-old from Zhengzhou, a metropolis of more than 4 million people in central China.

Fan, who had a diploma showing he’d earned degrees in computer engineering from the elite Tsinghua University in Beijing, had done some work for Chen and Li in China, and Greschner said he accepted his lover’s idea that Fan would be a good man for getting the facial recognition program up and running at the intelligence center.

As a result, Hummingbird, without vetting Fan further,sought his work visa, Greschner said, adding that he assumed law enforcement or other government officials took a closer look at the Chinese national. Greschner said he was asked by an official with the sheriff’s department in 2006 to provide a numeric code for Fan’s name, often used in investigations to pinpoint Chinese identity, which he did. In the application, Greschner said that Fan possessed skills not readily available in the U.S.

The Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office endorsed Fan as well. In a September 2006 letter to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, a senior sheriff’s official wrote that Fan already “demonstrated an extensive knowledge of the esoteric science” that converts human faces into data points. Such knowledge “appears to be” scarce.

Officials at the intelligence center discussed the wisdom of hiring a Chinese national for such sensitive work, according to Beasley, the counterterrorism director for the state’s public safety department. Beasley said he opposed it without success.

“Was there a concern? Absolutely,” Beasley said, “because China is not our friend.”

Cindy Bonomolo was the sheriff’s deputy most often assigned to monitor Fan inside the intelligence center.

“I was told he did the facial recognition for Tiananmen Square,” Bonomolo said in a June interview. “They said he was the best of the best. I have to say, this man was a genius.”

Greschner said Fan looked quite at home in the center.

“It was like ‘I was a member of the club’ – you know what I mean?” Greschner said of Fan.

Bonomolo’s ability to judge Fan’s talent or oversee the integrity of his daily work in the intelligence center was not great. She’d chiefly served as a patrol or corrections officer within the sheriff’s office. In an interview, she said she has no knowledge of computer science. Bonomolo said she had no reason to distrust Fan, and the two became close over discussions about her Christian faith. Fan became a Christian while in the U.S., she said.

Much of Fan’s job involved moving terabytes of data to servers. There were driver’s license records from the state, arrest files from county jails and criminal history data that had to be uploaded. Next, Hummingbird needed Fan to edit the facial recognition software so that it could reliably search all those different databases.

Fan had access to the center’s main network, according to three sources with first-hand knowledge of Fan’s work arrangements. From there, he would have been able to see the directory of federal agents and state police working at the Arizona counterterrorism center, said Haney, the retired immigration agent.

Thus, day after day, Fan enjoyed the rarest of access to confidential personal and investigative files.

Then, on the first Tuesday of June 2007, according to a former law enforcement official, Fan paid cash for airfare to Beijing at the Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport ticket counter. Fan’s luggage, Greschner and Li said, carried two laptops and additional hard drives.

Greschner said he and Li were out of town and unaware of what happened until days later. Greschner made his way to Fan’s rental home and powered on the Hummingbird computers that Fan had left behind. The drives were so thoroughly erased Greschner said he had to reinstall their operating systems.

Li attempted to contact Fan, to no avail.

However, Bonomolo exchanged occasional emails with Fan until losing touch in 2010. Fan’s first email to her from China alleged that Hummingbird regularly failed to pay his salary, so he felt justified taking the firm’s source code.

However, Bonomolo exchanged occasional emails with Fan until losing touch in 2010. Fan’s first email to her from China alleged that Hummingbird regularly failed to pay his salary, so he felt justified taking the firm’s source code.

“The whole event has had great impact on my family and my career, and we have been under gross pressure,” Fan wrote in a December 2007 email. The messages contain few other specifics about his work at the intelligence center. He told Bonomolo that his wife gave birth to a son and that he considered returning to the U.S.

“I do think about go (sic) back to the U.S. in a few years,” he wrote in his last message in November 2010, “and I’d like you to teach me how to shoot.”

No one has reported hearing from Fan in more than three years.

A Lack of Disclosure and Consequences

What exactly happened after Fan’s departure remains the least clear aspect of the entire episode. Some officials within the intelligence center became aware of his absence, and at least one expressed worry about its potential implications. Halliday, who ran the center at the time, called one of the center’s initial founders, Beasley.

“I’d say he was concerned and rightfully so,” Beasley said of Halliday.

For his part, Hendershott, the No. 2 man at the sheriff’s office, was concerned about keeping the potential embarrassment from becoming public, according to documents. One email exchange shows that Hendershott contemplated reaching Fan in China and paying him to stay quiet.

“Make sure that he knows that I just want your stuff and no trouble,” Hendershott wrote to Greschner, the Hummingbird executive who had hired Fan. “Just want him to go away. Can he and his wife keep their mouth shut?”

Over the years, there has been an array of breaches involving government agencies and people’s personal information. Typically, they have resulted in substantive investigations and notification of the public. Recently, for instance, The Washington Post reported that a “major U.S. contractor that conducts background checks for the Department of Homeland Security has suffered a computer breach that probably resulted in the theft of employees’ personal information.” The company, U.S. Investigations Services, said in a statement that the intrusion “has all the markings of a state-sponsored attack.”

The company did an internal examination to confirm the breach. The company notified the Department of Homeland Security, and the agency initiated its own investigation. As well, Homeland Security and the company alerted the affected people and disclosed the breach to the public.

In Arizona, no one will say if anything like that kind of effort was undertaken after Fan returned to China.

CIR and ProPublica, however, have learned that both the FBI and federal immigration authorities began to investigate Fan’s two Chinese associates – Li and Chen.

Paul Haney, the former Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent, said the FBI strongly suspects Li is a spy. The suspicions, according to Haney and others interviewed during the investigation, grow out of Li’s contacts with powerful people and institutions in China, and her efforts to help bring American security technology to her native country. As well, a delegation of Chinese airport officials organized by Li, which came to the U.S. to tour security facilities, included at least two people who were, in fact, not airport officials.

“If she is who we think she is,” Haney said, “she’s a professional.”

Paul Moore, a former top FBI Chinese counterintelligence analyst, said cultural differences between the West and East pose challenges for investigators trying to determine if Chinese are involved in intelligence operations.

“Was this a Chinese intelligence operation, or just something that came in over the transom?” he said. “It sounds like Chinese people acting like Chinese people. It looks foreign to us — and suspect.”

The authorities have never charged either Li or Chen with espionage, and in interviews both have denied the assertion. The authorities, however, did successfully detain and then deport Chen on immigration fraud charges, claiming he had set up a fake business in the U.S. as a way of obtaining a green card. And they are using an unusual charge in seeking to strip Li of her American citizenship and send her back to China: bigamy. The government has claimed in court documents that Li was married to more than one man at the same time during her time in the U.S. Li is contesting the charge, and she insists one of the marriages amounted to a mock ceremony meant to appease her partner’s parents.

“I’m not a spy, so I can’t tell you why they suspect me,” Li said.

Li, in fact, offers her own theory for why the government is eager to deport her: She has knowledge of the possible security breach in Arizona.

“It could be a very big embarrassment to the governor (Napolitano) and to the sheriff’s office as well,” she said.

Greschner and Li no longer live together but remain a couple.

Napolitano is now president of the University of California system. Arpaio remains an outsize and divisive figure in Arizona. As for Hummingbird, it appears to have lost several contracts with Homeland Security after Fan’s departure. But it did, for two years after the episode, continue its dealings with the sheriff’s office.

That finally ended in 2009, when the company folded.

Michelle Van Cleave, a U.S. national counterintelligence executive under President George W. Bush, said under no circumstances should a foreign national from any country, let alone from China, be allowed inside an intelligence facility. The risks of information being compromised are too great, she said.

Of the saga of Fan and the Arizona intelligence center, she said: “It’s just stunning.”

The Center for Investigative Reporting and ProPublica collaborated on this story. Ryan Gabrielson is a former CIR reporter who has since moved to ProPublica. To learn more about CIR and ProPublica, visit cironline.org and propublica.org.

Becker can be reached at abecker@cironline.org. Follow him on Twitter @abeckerCIR. Gabrielson can be reached at ryan.gabrielson@propublica.org. Follow him on Twitter @ryangabrielson.