In the mid-to-late 1980s, Nevada’s state-run workers’ compensation insurance system was scaring its actuaries.

Their job was to calculate whether the State Industrial Insurance System (SIIS) would have enough money, down the road, to pay the injured-worker liabilities it was taking on.

And more than one of the actuaries were telling SIIS insiders, “Listen: We’re in trouble.”

One part of the problem was that, for multiple years, premium rates (the charges to businesses for their compulsory participation in SIIS) had  remained unchanged — even though SIIS was awarding some of the most generous benefits in the Western states.

remained unchanged — even though SIIS was awarding some of the most generous benefits in the Western states.

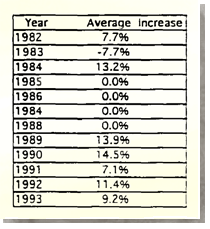

“For 14 years,” Sen. Randolph Townsend told fellow lawmakers in May 1995, “we did not collect enough premium to cover our expenses.” Citing numbers provided by the state Division of Insurance, the then-chairman of the Senate Committee on Commerce and Labor itemized nearly half a billion dollars of work-comp premium that businesses had owed, but which SIIS had failed to collect:

1982: $44 million.

1983: $68 million.

1984: $58 million.

1985: $71 million.

1986: $87 million.

1987: $74 million.

1988: $65 million.

Moreover, while SIIS costs had continued to escalate in the 1985-1988 years, said Townsend, “not one dime of increase in premium … occurred.”

That policy, according to former assemblyman Phil Stout, who headed the Nevada Association of Independent Businesses for many years, reflected a SIIS board consensus managed by Claude “Blackie” Evans, secretary-treasurer of the state AFL-CIO.

Appointed and re-appointed by three successive Democratic governors — Mike Callaghan in the late 1970s, Richard Bryan in the 1980s and Bob Miller in the early 1990s — Evans “became pretty much the main person on the board,” Stout told Nevada Journal in a 2001 interview.

“And so, when they put new people on the board, they were pretty much his supporters. Even though it was broken down so that you had to have three Democrats, three Republicans and three independents from at large … he would see that the people who were put on the board would at least give him a majority all of the time.”

Evans, said Stout, “was constantly voting to give more money to the injured workers, and getting legislation passed to allow that, and letting more people of lesser injury get more money.” But while “he kept allowing that to happen, he wasn’t charging the employer enough money to cover the total costs of what SIIS was putting out.”

At the same time, a Las Vegas building boom was increasing exponentially the number of benefit claims facing SIIS. A former employee of SIIS told Nevada Journal:

I remember talking to some employers and saying, ‘I’ve looked at some figures here on injuries in the construction industry. What’s going on?’ And they said, ‘There’s so much competition here…, if a guy can swing a hammer, we’ll hire him and we’ll send him out on the job. And we try to give him a little bit of job training, but some of these guys don’t know how to handle a SkilSaw, or a nail gun, and they’re getting hurt out there because they’re not trained.’

By 1989 claims had risen to 80,000 annually — from about 20,000 a year earlier in the decade.

Making matters even worse, costs per claim were also quickly increasing. In Nevada, as all across the country, health care pricing was already launched on what would be a sustained, decades-long rise.

A perfect financial storm was gathering.

In Carson City, however, key government functionaries — lawmakers and bureaucrats — didn’t want to hear what the actuaries were saying. The actuaries were being ignored — militantly.

It was politics in action: Nobody wielding authority within the state bureaucracy, the state legislature or the Nevada governor’s office wanted to be publicly identified with any call for higher premiums to be paid by business, or for lower workers comp benefits.

So the problem grew worse.

Throughout state government, there was no shortage of reasons for people to duck and cover.

Within the state insurance division and SIIS, it was understood that higher rates could make employers push lawmakers even harder to end the state monopoly on workers’ comp insurance and let private insurance carriers compete. The idea was called “three-way insurance” — workers’ comp insurance available from either SIIS, self-insurance or from private insurance companies.

Already, in 1980, Nevada’s largest public and private employers had been allowed by the Legislature to go down the self-insurance road. Now, if virtually all companies were going to have access to private carriers, SIIS itself could find itself out of job — as also could many of the agency’s approximately 900 state employees.

Like the state industrial-insurance establishment, organized labor had reasons for resisting the three-way insurance idea.

Because workers’ comp was still primarily a government-monopoly system, labor’s political strength — exercised through elected state officers and lawmakers — gave it maximum leverage and control. Much of that control would disappear, however, were labor to find itself facing thousands of individual companies.

Such realities weren’t lost on the administrations of the two Democratic governors during the 1980s, Richard Bryan and Bob Miller. State workers and organized labor, after all, made up much of their party’s political base.

Lawmakers, regardless of party, were similarly sensitive. Making them even more so was an odd statute in Nevada law: It required applications for rate increases to be filed at the beginning of the legislative session — ensuring that rate hikes would become high-profile political issue, arousing passions and putting lawmakers on the spot.

In the run-up to the 1989 session, however, SIIS actuaries were saying that rate hikes could no longer be delayed.

Claims-examiner caseloads in Nevada were running far above the norms for any other state-run workers’ comp systems in the country — as much as 300 claims per examiner, when the standard per examiner was about 25.

“When you’re that far over the standard workload,” said the former employee, “you can’t do a good job.

“[T]here were people who were staying on comp longer than they should have, because the claims examiner couldn’t manage the claims effectively enough to make sure that they got [the injured worker] to a consulting doctor to see if he should be sent back to work yet. We had people that would be on occupational rehab for a year with no program yet…

“And we asked repeatedly, ‘Can we hire more staff?’” — at the same time pointing out that, “’We pay for it out of our premium, not out of general taxes.’ Again, it became a political issue. The answer was no.”

When staffers contacted leaders of the Senate Commerce and Labor committee to give required notice — that the system needed, at the very least, a 7 percent increase in the coming fiscal year, and something like that again for the year after that — the reaction was fierce.

“You take that notice back to your manager today,” then-senator and assistant majority leader Leonard “Len” Nevin (D-Carson City) was reported to have said. “And you tell him to tear it up. Because if he doesn’t, by tomorrow we’ll have a bill through both houses and on the governor’s desk to prohibit you from raising rates.”

Eventually breaking that logjam — but also precipitating the eventual end SIIS itself — was, of all people, the blunt-talking Evans:

Blackie Evans recognized [says the former SIIS employee:] that you can’t run a railroad this way. And he went, I believe, privately to the governor and tried to persuade him: “Let us hire enough people to do the job accurately and make sure somebody is ready to go back to work, [and that] we get him back to work, because [SIIS is] bleeding money when [workers are] sitting there at home, and we haven’t got them back to work. And, we’re not adequately supervising the doctor[s].” But the governor came out — and there was a hiring freeze at that time — and he said, “Nope. The hiring freeze applies to SIIS as well.”

Evans’ basically challenged Miller directly, reportedly saying at a public meeting of the SIIS board:

“It’s not coming out of your money, your tax money. If we don’t get these people, we can’t do our job. And, we have been told by your budget director that ‘ain’t gonna happen.’”

“Well, politically, of course, the governor had to take some action,” continued Nevada Journal’s source. “And so, the next day, there was a press release saying, ‘I don’t know where those guys at SIIS got that idea, but we never said they couldn’t hire. Of course they can hire. They’re idiots. They should have been hiring all along.’”

“Behind the scenes, it became apparent that you don’t make the governor, or any person in a high political position, look bad. And I think that was the beginning of the governor’s desire to abolish the board and take over the place himself.”

With the workers’ comp shortfall now a fully public issue, the obvious political question was: Who’s going to get stuck with the blame?

Assembly Speaker Joe Dini (D-Yerington) put in a bill requiring the legislative auditor to audit the entire workers’ comp system — SIIS, oversight of the self-insured, and the Department of Administration, which conducts the work-comp hearings and appeals.

The legislation was Assembly Bill 1. “When you’re AB 1,” observes the former SIIS insider wryly, “you know that somebody is paying a lot of attention to you.”