In 2004, the Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department commenced an aggressive campaign to promote what was called the “More Cops” Sales Tax Initiative.

Citing standard law enforcement metrics as evidence the agency was understaffed, Metro P.D. marketed the initiative as the most effective way to secure the hiring of more uniformed police officers to serve the Las Vegas basin.

Specifically, Metro noted that its officer-to-population ratio — measured by officers per 1,000 people served — was lagging relative to the national average.

Metro’s arguments throughout 2004 convinced Clark County to vote “yes,” by a narrow margin, on an advisory ballot question, which asked the following:

Do you support an increase in the sales and use tax in Clark County of up to 1/2 of 1% for the purpose of hiring and equipping more police officers to protect the citizens of Clark County?

With a documented majority of support, Metro P.D. then took its campaign to Carson City, where it advocated for the passage of the Clark County Sales and Use Tax Act of 2005 before legislative committees.

The bill garnered enough support to be passed into law and, by October 2005, law enforcement agencies in Clark County began receiving tax revenues distributed in proportion to the populations each agency served.

Now, in 2016, Metro is not meeting its hiring projections for new, uniformed officers despite having the funds to do so from the More Cops revenues.

While Metro projected that the More Cops revenues would support the hiring of 1,278 new, uniformed officers by the end of 2015 — an estimate it labeled as being “conservative” — it had hired only 566 through that date.

It is fair to note that Metro did not receive the full tax increase for which it campaigned — after enacting an initial .25 cent hike to the Clark County sales tax, the legislature declined to authorize the additional .25 cents for which police agencies throughout the county had been hoping.

Notwithstanding the failed attempts to acquire the full .5 cent increase (Metro ![]() currently enjoys the revenues of a .3 cent increase), this fact is somewhat moot given that Metro’s lack of hiring seems to have not resulted from a lack of funds. To the contrary, Metro maintains significant cash stockpiled from the More Cops revenues.

currently enjoys the revenues of a .3 cent increase), this fact is somewhat moot given that Metro’s lack of hiring seems to have not resulted from a lack of funds. To the contrary, Metro maintains significant cash stockpiled from the More Cops revenues.

Metro’s focus, it appears, has largely been on the question of what funding will be in place after the More Cops authorization is scheduled to expire in 2025. Reports from inside the department suggest strong concerns that, in nine years, the multimillion-dollar revenue stream from the sales-tax levy might not be reauthorized and so might actually come to a sudden stop.

This appears to be a primary reason why, for years, Metro had been banking the More Cops revenues, rather than immediately using available funds to put more police on the street.

Other factors, however, have also contributed to what might be termed the “underperformance” of the More Cops Sales Tax Initiative:

1) The information used to sell the More Cops initiative to voters and lawmakers was riddled with errors, thus endangering expectations based on that information.

2) The funds produced by the sales tax have been underutilized.

3) Per-officer costs have increased sharply since the 2004 campaign and the 2005 legislative authorization.

A campaign riddled with inaccuracies

Throughout its advocacy before legislators, Metro and other More Cops supporters used information that was less than accurate, coupled with rhetoric that misled.

First, Metro based much of its argument on the rate of population growth seen in Clark County throughout the 1990s and early 2000s.

In its 17-page PowerPoint presentation offered to the Assembly Committee on Growth and Infrastructure on April 5, 2005, Metro claimed that “police departments have struggled to meet the needs associated with growth through their normal budgetary processes.” It was further claimed that “funding has not kept pace with the demand for services with Southern Nevada.”

An actual check of the record, however, reveals that Metro P.D. funding not only had kept pace with population growth in the decade before the More Cops campaign, it had actually outpaced it:

![]() Between 1995 and 2004, funding for Metro P.D. increased by approximately 75 percent. During that same period, Metro’s served population increased by only 57 percent, belying Metro’s claim that population growth had outpaced increases in Metro’s funding.

Between 1995 and 2004, funding for Metro P.D. increased by approximately 75 percent. During that same period, Metro’s served population increased by only 57 percent, belying Metro’s claim that population growth had outpaced increases in Metro’s funding.

Secondly, Metro repeatedly claimed that crime was on the rise in Clark County over recent years, claiming specifically, in the same PowerPoint presentation, that “major crimes continue to increase.”

This claim deserves close inspection. While raw numbers of crimes undeniably increase with a growing population, the more serious issue concerns the crime rate. Is the actual crime rate across the population served increasing or decreasing?

![]() What the documented longer-term trend actually illustrates is a consistent, steady reduction in the crime rate throughout the decade prior to Metro’s 2004-05 campaign, though marred somewhat by an uptick in the combined rate reported for three of the final four years. Between 1995 and 2004, the rate of crime actually decreased by 26 percent within Metro’s served population.

What the documented longer-term trend actually illustrates is a consistent, steady reduction in the crime rate throughout the decade prior to Metro’s 2004-05 campaign, though marred somewhat by an uptick in the combined rate reported for three of the final four years. Between 1995 and 2004, the rate of crime actually decreased by 26 percent within Metro’s served population.

![]() A critical

A critical ![]() question would be: Where, exactly, was the increase in crime occurring? A look at UCR data reported by Metro to the FBI and the State of Nevada indicates the answer is auto theft, where a 30 percent jump was reported.

question would be: Where, exactly, was the increase in crime occurring? A look at UCR data reported by Metro to the FBI and the State of Nevada indicates the answer is auto theft, where a 30 percent jump was reported.

A final inconsistency throughout the More Cops campaign concerns Metro’s promised use of its sales-tax revenues.

As its name suggests, the “More Cops” Sales Tax Initiative promised to use any associated funds for the exclusive purpose of hiring more uniformed police officers.

In the PowerPoint presentation given 2005 lawmakers, Metro — as did other police entities and multiple city and Clark County officials — pledged that “funds will be used only to hire and equip new police officers.” (No emphasis has been added to that sentence. Metro itself underlined the word “only” in its campaign documents.)

Subsequently, as passed, the language of Assembly Bill 418 permitted local Clark County governments to “enact an ordinance imposing a local sales and use tax to employ and equip additional police officers.”

In the same section, the legislation mandated that “the proceeds from the tax authorized pursuant to this section . . . must be . . . used only as approved . . . and only for the purposes set forth in this section unless the Legislature changes the use.”[1]

Later, however, Metro faced a significant budget deficit for the 2014-15 fiscal year. It then quietly and successfully lobbied the state legislature for permission to breach this promise — the frequently repeated public pledge used to gain public approval of the More Cops tax.

Under the exception authorized by state lawmakers, Metro was allowed to move the costs associated with 152 previously hired officers over to be paid out of the More Cops fund.

Subsequently, Metro’s own Fiscal Affairs Committee unobtrusively green-lighted this action under its pro forma “consent” agenda. The total additional costs paid out of the More Cops revenues totaled $18.9 million for fiscal year 2015.

In this fashion, citing post-Great Recession exigencies, Metro P.D., the county and the cities reneged on their many promises to taxpayers to only use the More Cops dollars for additional police on the street.

Afterward, the money chase has continued.

In February 2016, immediately following Metro’s successful lobbying of an additional .05-cent increase in the More Cops sales tax, Metro nevertheless asked Clark County for an additional $10 million for its 2017 budget.

Similar funding requests have occurred since, notwithstanding the many millions of dollars that Metro holds in reserves.

Have those reserves been underutilized?

Underutilization of More Cops revenues

As recently analyzed by Nevada Journal (see “Metro’s More Cops spending policy unclear…”), Metro’s More Cops revenues quickly after 2005 piled up an enormous bank balance. Yet that fund was essentially sequestered and remained basically untapped for a decade.

Clark County Fund 2320, specifically established to hold Metro’s share of More Cops funds, maintained an end-of-year balance of $43 million after only its first year of collecting revenues. The fund’s balance has steadily increased in the years since.

By the end of 2014, Fund 2320 held $136 million in available, unused funds earmarked for the hiring of new, uniformed police officers. (By the end of 2015, that balance did decrease to $113 million, but this reflected the approximately $19 million in general-fund costs for which the More Cops fund was tapped, as mentioned above.)

That Metro maintains such an enormous balance is noteworthy for two reasons: Metro continues to lobby Clark County and the City of Las Vegas for additional funding despite its own stockpiled funds, and Metro has failed to meet its projections in terms of new officers hired.

![]() In this sense, Metro appears to be making a conscious choice to not utilize its available funds, opting instead to “save” what funds it currently has for reasons that aren’t entirely clear.

In this sense, Metro appears to be making a conscious choice to not utilize its available funds, opting instead to “save” what funds it currently has for reasons that aren’t entirely clear.

Excluding 2015, the year in which general-fund costs of 152 officers were “supplanted” to Fund 2320, Metro hasn’t utilized more than 35 percent of its available funds in any given year towards its stated purpose of hiring more uniformed police officers.

At least one likely reason is apparent.

Per-officer costs have skyrocketed since the 2004-05 campaign

Since 2004, according to Metro’s calculations, per-officer costs have increased sharply.

Whereas the cost to hire, train and equip a first-year officer was reported as approximately $90,000 in 2004, now per-officer costs in 2016 are 28 percent higher, having jumped to $115,000.

Thus, because the long-term costs of hiring even a first-year officer are now so much greater, those costs constitute disincentives facing the department as a whole that are significantly greater than existed a decade ago.

![]() Moreover, those per-officer costs appear unlikely to decline, given recent, post-2005 increases in the public-pension contribution rates for police and fire employees that Nevada’s taxpayers now must bear on Metro P.D.’s behalf.

Moreover, those per-officer costs appear unlikely to decline, given recent, post-2005 increases in the public-pension contribution rates for police and fire employees that Nevada’s taxpayers now must bear on Metro P.D.’s behalf.

Between 2005 and 2016, the required contribution rate for police officers increased from 28.5 percent of their salaries to 40.5 percent, or by 42 percent.

In other words, the annual, taxpayer-funded retirement costs for 100 officers now equals the salaries of 40.5 additional officers.

While the current pension-contribution rates appear exceptionally lucrative for existing public-safety employees in the PERS system, that’s only so long as local governments can continue to make the payments. Already the system — the richest in the country for public employees — is, in the eyes of many experts, too Ponzi-like to be sustainable.

Moreover, the day of its failure would seem likely to advance with each new young officer joining the department, given some of the increasingly heavy costs associated with each officer.

Is this an unacknowledged reason why Metro, effectively, has deferred use of the More Cops dollars for actually expanding its force?

It would seem entirely understandable that some individual Metro officers may indeed have mixed feelings about bringing new, younger officers into the department. Do they worry about their own pensions being at risk when the burdens on PERS become unsustainable? Do they see new officers as conceivably hastening the date of PERS’ failure?

Metro P.D., of course, has no direct, unilateral authority in the setting of these contribution rates. But its associated police officers union, the Las Vegas Police Protective Association, has long aggressively bargained for increasingly generous retirement benefits.

This fact, coupled with Metro’s reluctance to fully utilize its More Cops fund for its intended original purpose, suggests that Metro may be more concerned with maintaining its employees’ already-generous retirement packages than with hiring more officers.

Nevada Journal asked Metro P.D. about the impact of the rising per-officer costs on department hiring but received no response.

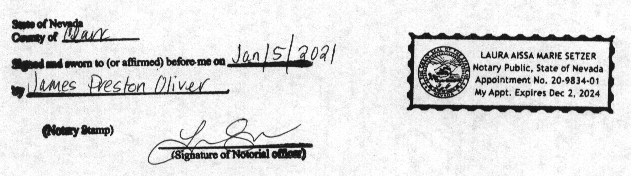

Daniel Honchariw, MPA, is a public policy analyst with the Nevada Policy Research Institute.