During the early 20th Century, in every American state save Texas, politicians and politically active special interests — some ostensibly representing labor and others business — passed into law compulsory systems of industrial insurance.

Moreover, even in Texas, longstanding common-law principles of liability and individual responsibility were overturned.

While these new compulsory state social-insurance systems offered advantages to some employers and some employees, all members of both groups were deprived of certain rights that formerly had been considered inalienable.

What had facilitated such a fundamental repudiation of longstanding American principles? It was the conjunction of a recently emerged “progressive” consensus with an opportunity for its imposition: a perceived crisis of widely reported industrial injuries.

The German infatuation

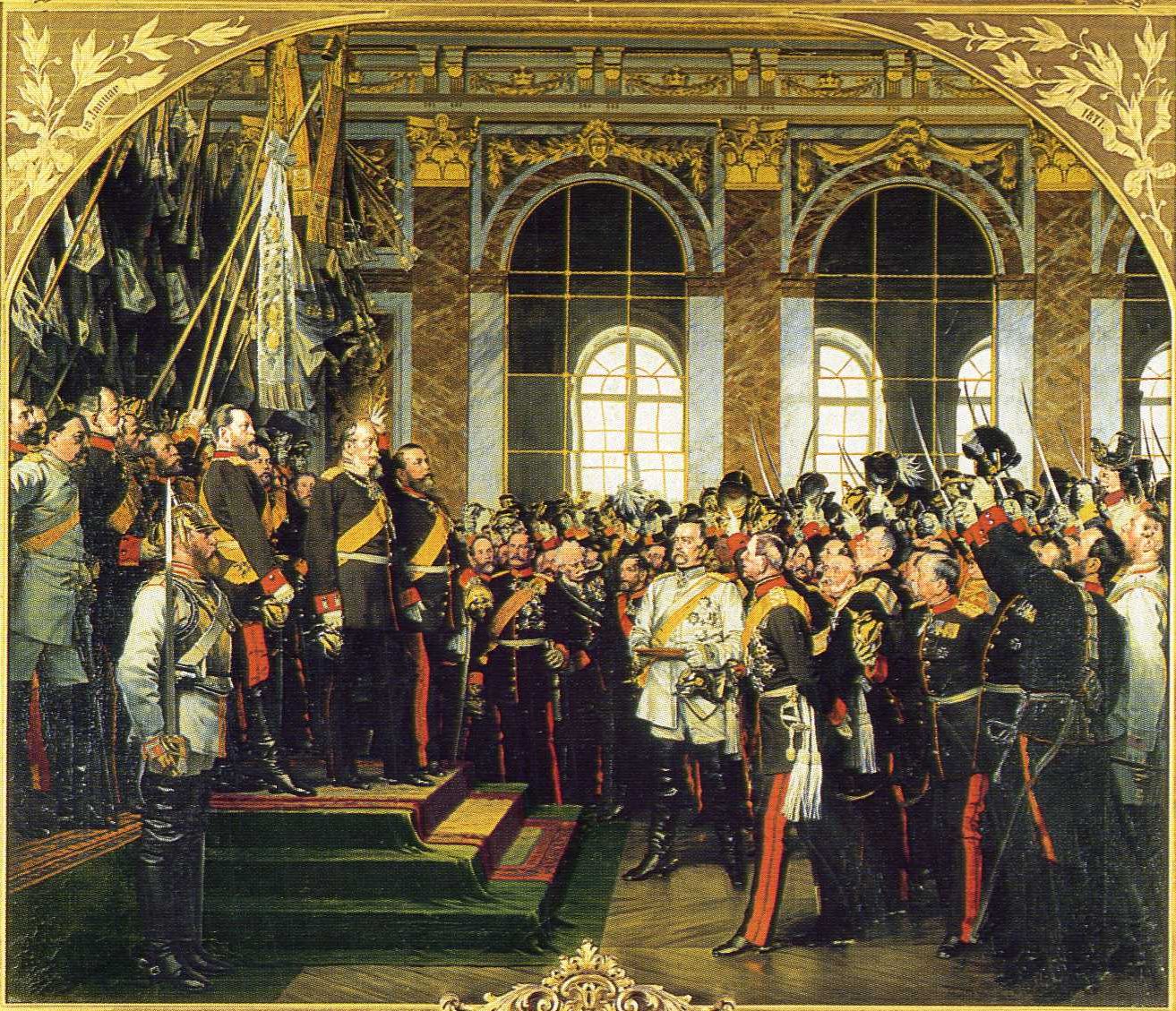

Neither the consensus nor the “crisis” was quite what it seemed. The former — a growing fatigue with laissez-faire liberalism that had been accelerating toward the end of the 19th Century — was the flip side of a rising enthusiasm for Prussian-style schemes to use the centralized state as an engine to drive compulsory “reforms.” Following militarist Prussia’s swift victory over France in the Franco-Prussian war, imperial-minded Americans increasingly admired the Bismarckian state.

German statist ideologies also titillated certain disaffected 19th Century U.S. elites. The American Economic Association, for example, explicitly parroted Hegel’s doctrine that “The state is the actuality of the ethical Idea” when it founded itself, in 1884, upon a platform declaring:

We regard the state as an educational and ethical agency whose positive aid is an indispensable condition of human progress.

It was that very year that also saw the legislative birth in Prussia of state-mandated workers’ compensation.

As known today in the U.S., however, that traditional answer to the problem of injured workers is beset by multiple and growing challenges. On the one hand, as documented by ProPublica and others, the benefits for injured workers supposedly available from the workers’ comp “grand bargain” have for decades been shrinking — raising the issue of whether what remains, especially in certain states, is even constitutionally sound.

At the same time, “opt-out” alternatives arguably superior to traditional workers’ comp — seen from the standpoints of both employees and employers — have emerged in Texas, Oklahoma and Tennessee.

These alternatives, in many ways, reconsider and re-answer the original questions asked during the original birth pangs of workers’ compensation in 19th Century Prussia.

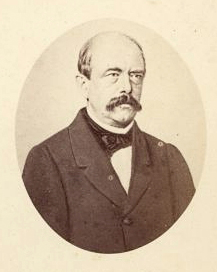

Often romanticized today and attributed to the good will and progressive instincts of the chancellor and minister-president of Prussia (and Germany) at the time, Otto von Bismarck, the actual reality was significantly less ideal. John M. Kleeberg — whose deeply researched inquiry into the historical particulars behind the 1884 law was published by the New York University Journal of International Law & Politics in 2004 — concluded:

Often romanticized today and attributed to the good will and progressive instincts of the chancellor and minister-president of Prussia (and Germany) at the time, Otto von Bismarck, the actual reality was significantly less ideal. John M. Kleeberg — whose deeply researched inquiry into the historical particulars behind the 1884 law was published by the New York University Journal of International Law & Politics in 2004 — concluded:

Social insurance did not arise from the moral benevolence of Otto von Bismarck, but from the crude horse-trading known to us from public choice theory.

Moreover, even beyond its political-horse-trading origins, American workers’ comp bears the marks, still today, of Bismarck’s personal involvement in its passage. If not for his own financial self-dealing, his well-documented deceitfulness and his obsession with ensuring absolute power for the feudalistic Prussian monarchy — which he dominated — the entire history of industrial insurance in the Western world could well have turned out very differently.

The perceived crisis

Prussia, in the early years of the Industrial Revolution, was a natural place for the issue of industrial injuries to first gain prominence. That state had, at the time, the most built-out railroad mileage of any country in the world.

The extent of the railroads in Prussia reflected that state’s grant of its powers of eminent domain to railroad firms, in which the state itself was also often a large investor. The Prussian monarchy — for centuries occupied by kaisers who saw themselves as military leaders first — saw railroads in terms of their utility, in case of war, for quickly moving armies.

Similarly well-developed in Prussia for that era was the mining of iron and coal — also fostered by the state.

While these “new industries actually may have been safer than the old agricultural economy,” notes Kleeberg, “what was new … was the mass accident and the publicity it engendered.”

Naturally enough, what soon followed was the world’s first modern strict-liability act: the 1838 Prussian Railroad Law. It sought to make railroads financially responsible for any damages arising from the presence of the railroads, on the argument that the railroads were inherently dangerous.

The 1838 act originally had been intended to simply protect passengers and Prussian landowners — the latter worrying that engine sparks might set their fields or barns afire. At the start, the act did not address employee accidents.

The railroads’ new financial liability was actually not that burdensome, since the lines were already quite profitable. Moreover, the strict liability rule — which was seen as just, given the state-granted privileges wielded by the railroads — simply led the firms to purchase insurance. Additionally, because the strict-liability burden now constituted another disincentive for new entrants into the railroad business, market competition for the initial firms was slow to arise — keeping their profits up.

Over time, however, Prussia’s highest court began significantly reinterpreting the 1838 law, notes Kleeberg:

By the end of the 1860s the Prussian courts had changed the character of the Prussian Railroad Law. Originally designed for a state dominated by the Junkers and intended to favor the landowners, it had metamorphosed into a social measure to help the industrial proletariat.

The Prussian Supreme Court had essentially rewritten and expanded the 1838 law. To understand the background requires recognizing the underlying turmoil afflicting Prussia — and Germany in general — throughout the 19th Century.

Napoleon, bearing the standard of a more rational version of the French Revolution, had been greeted as a liberator throughout much of Germany. His shattering victories at Jena and Friedland, occupation of Berlin and the subsequent gelding of Prussia in the Treaty of Tilsit had revealed the Hohenzollern military dynasty as only a corrupt and empty shell.

Prussia’s revival, over the next several years, was, ironically, led by non-Prussians who pushed through domestic reforms, such as the abolition of serfdom, and the creation of the Landwehr, the people’s army that proved itself at Leipsig in 1813 and at Waterloo in 1815. The traditional masters of Prussia, the Junker landowners, had actively opposed both reforms.

So Prussia and the reigning Hohenzollern dynasty were — at the very least — quite fearful of the possibilities of a people’s revolution from below — one that would impose constitutional limitations on the dynasty and secure broad human rights for ordinary Germans.

Moreover, it had been a near thing during the “Revolutions of 1848,” amid the near-revolutions sweeping Europe, when the Prussian dynasty, with all its hangers-on and autocratic political structure was almost overthrown.

However, as Kleeberg writes, the Prussian ruling classes had learned from that experience “that the bourgeoisie could not succeed in staging a revolution without the support of the handicraftsmen and the industrial proletariat.”

“Under the reactionary Manteuffel regime of the 1850s, the Prussian government sought to favor these two classes in order to keep the liberal bourgeoisie in check.”

It was to be expected that Supreme Court justices appointed by the dynasty and its defenders would keep the interests of the monarchy in the forefront of their concerns. Over the next forty years, however, that imperative would be even more explicitly clear to the courts.

The arrival of Bismarck

Biographies of Bismarck, who became minister-president in 1862, demonstrate repeatedly that what he brought to the task of undercutting the forces of liberal reform was a much more supple and unprincipled intellect than Manteuffell could ever muster. Edward Crankshaw’s Bismarck, as does Jonathan Steinberg’s Bismarck: A Life, well documents the rampant fear of the threats that laissez-faire liberal ideas posed for authoritarian Prussia, in Bismarck’s mind, at least.

Writes Crankshaw:

At a time when the rest of Europe, including most of Germany (Baden, Württemberg, Bavaria, Saxony), the great Austrian Empire, even Russia for a brief spell, was moving towards greater individual freedom, a deeper sense of individual dignity and a new understanding of the constructive  forces latent in those who were not born to rule, Bismarck was systematically transforming Prussia into a police state… He operated thus with one purpose only — to subdue the Prussian people for the enlargement and glorification of the Prussian state.

forces latent in those who were not born to rule, Bismarck was systematically transforming Prussia into a police state… He operated thus with one purpose only — to subdue the Prussian people for the enlargement and glorification of the Prussian state.

Thus, after the 1863 election he shocked the nation by the savagery of his assault on all who had exposed themselves by speaking out against his policies. Parliamentary deputies of distinction, as well as unsuccessful candidates, were heavily fined for attacking the government in their election addresses. Manufactories and businesses connected with opposition politicians were subjected to sanctions and deprived of government contracts; civil servants were dismissed; professional men with a liberal cast of mind were excluded from government appointments.

A very important landmark was passed in May 1864 when the king reluctantly agreed that judges should be advanced not on grounds of seniority but in recognition of their political soundness. The liberals fought back but Bismarck rode them down, using the bureaucracy as though it was a private police force; senior civil servants carried out his command in a spirit of obedience that was very close to servility. Thus, when a liberal was elected mayor he would find the government refusing to confirm his appointment, a government agent being set up in his place. Most of the lower courts were presided over by liberals, but virtually all high court judges were conservatives, able and eager to overrule the lower courts in every case which had a political aspect. When the minister of justice himself, Count Leopold von Lippe, protested against this suborning of the judiciary Bismarck retorted as a matter of course that it was the business of the government to reward its friends and punish its enemies.

By 1865 things had gone so far that he felt strong enough not merely to talk down, override, or simply ignore the most articulate of the parliamentary objectors to governmental lawlessness but actually to prosecute two distinguished deputies of the Lower House, Twesten and John Peter Frentzel, for protesting, as deputies, in the Chamber itself, against the erosion of constitutional rights. (Emphasis added.)

This explains much of what was happening in the Prussian judiciary during the 1860s and later. The courts were increasingly reflecting the priorities of Bismarck.

“[D]eliberately emphasizing all the most backward aspects of the Prussian ethos,” writes Crankshaw, Bismarck “so demoralized his Prussia (as later all Germany) that she was led ever further away from the mainstream of west European development” — a process that would reach its natural, if horrific, culmination in the rise of National Socialism.

For Part 2, click here.