It’s common knowledge that, for over a century, state-mandated workers’ comp systems have held sway as the “exclusive legal remedy” available to victims of workplace accidents.

Frequently overlooked, however, is the extent to which the work-comp regime has also, by its compulsory nature, excluded alternative and innovative solutions to that very same problem: finding the best solution to the chronic problem of workplace injuries.

Workers’ comp thus operates as a particular case of the general rule that government, by making a particular solution mandatory, tends to freeze innovation in the area of that mandate.

Nevertheless, there is one state in the United States that never entirely abandoned the constitutional principles that prevailed before the wide embrace of Otto von Bismarck’s compulsory industrial-insurance model.

Notably, the state of Texas still proclaims its adherance “to the principle that employers should be allowed to choose whether to offer workers’ compensation benefits to their employees.”

On its website, the Texas Division of Insurance notes that in 1913, when the state enacted workers’ comp laws, “the courts generally held that mandatory, government-administered workers’ compensation programs denied the property rights of employers without due process of law.”

Four years later, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that states could require employer participation in a state work comp program, Texas chose to retain the voluntary option for employers.

Today, Texas is the only state that allows private employers to choose whether or not to provide workers’ compensation. And fully one third of them — 33 percent, according to the Texas Division of Insurance — choose not to.

This doesn’t mean, however, that these employers’ workers suffer under some Dickensian regime of abuse and penury. In Texas, employees of nonsubscribing employers retain their traditional common-law rights to sue for employer negligence, the same rights that are nullified under workers’ comp.

Thus Texas Option employers, facing a genuine negligence liability exposure that comes with the decision to nonsubscribe, have even more powerful incentives to ensure both worker safety and, when injury does occur, increased worker satisfaction.

The result — according to PartnerSource, a firm serving the “Texas Option” community for the past 25 years — is that workers receive better medical outcomes than under workers’ compensation, more attention to their issues and often higher wage-replacement benefits.

Usually, “an employer can and typically will take better care of injured workers, at a lower cost, in a free-market system than in a hyper-regulated, government-centric program,” observes PartnerSource President Bill Minick, in a 2015 white paper.

“Many employers that have elected the Option to nonsubscribe from Texas workers’ compensation over the past 25 years have invested heavily in, and substantially improved, their safety programs,” and “do so on an ongoing basis, in part, because of this liability exposure.”

In addition, notes Minick, the regulatory environment that employers face today is quite different than when U.S. states were first embracing worker’s compensation.

“Texas nonsubscription recognizes that we are no longer in the Industrial Age,” he says, observing that today, “Employers recognize employees as their best asset and strive to be recognized as a ‘Best Place to Work.’” Firms also “now have technological capabilities to access, gather, and utilize large amounts of data on their own.”

Another major factor, Minick points out, is that in the past 45 years many highly relevant federal laws have emerged that significantly impact the workspace. These include the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA), the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA), and the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA).

These laws, notes Minick, require substantial employer-employee communications, as well as protections against unsafe work environments, wrongful benefit denials, discrimination and employment termination.

For example, ERISA — which, as federal law, governs all private benefit plans under the Texas Option — “supplies an entire regime of employee protections,” he observes, adding:

The claims administrator and other plan fiduciaries must perform their duties solely in the interest of the covered employees and beneficiaries. When providing injury benefits and handling administration expenses, plan fiduciaries must follow a “prudent man” standard of care and must administer the plan in accordance with the plan documents governing the plan.

Moreover, for both workers and employers, writes Minick, ERISA provides claim procedures that are “typically much more simple and efficient than any workers’ compensation commission and court processes.” (Emphasis added.)

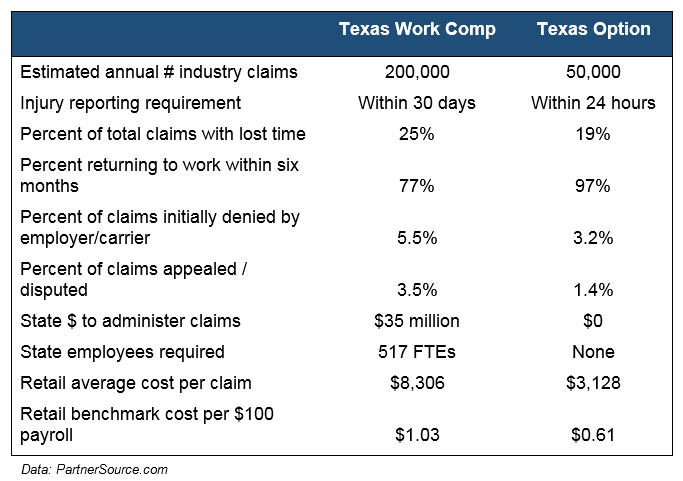

Overall, he argues, workers’ compensation is significantly outperformed by the Texas Option:

These results, writes Minick, flow out of the “broad, free-market competition with workers’ compensation insurance markets,” plus “a simple statutory framework of employee protections” and substantially increased “productive communication between employers and employees on their rights and responsibilities.”

The written injury benefit plans must specify definite determinable benefits. The employer must formally adopt that plan, and the plan terms must be fully communicated to employees in language they understand.

Employee accountability is improved through simple, logical injury reporting and medical management requirements that lead to better, more predictable medical outcomes.

“Unlike certified medical provider networks developed for workers’ compensation,” says Minick, “an Option to workers’ compensation is NOT about squeezing savings out of medical provider reimbursement rates. It is about paying fair reimbursement rates in exchange for a collaborative, open relationship focused on injured employee care.”

Nonsubscribers, in fact, “are often willing to pay more for the best provider. When employers and insurance carriers look at the total claims cost savings produced by the Option, there is no need to try to ‘nickel and dime’ medical providers.”

Consequently, providers prefer to work with firms that have taken the Option. And even when providers are paid at the same reimbursement rates as the Texas workers’ compensation system, they “come out way ahead,” Minick argues.

“Option program medical providers are not burdened with completing a myriad of reports and office personnel are not constantly on the telephone with insurance adjusters to get approval for treatment. The Option greatly simplifies paperwork and streamlines approval processes so that medical providers can be more focused on the delivery of quality medical care, less focused on workers’ compensation bureaucracy, and run a more profitable medical practice.”

The result is a much more smooth-flowing process for both workers and employers that saves money all around, says Minick.

“When employees are being well-cared for and have a high level of satisfaction with how they’ve been treated, we see fewer and faster resolution of disputes,” he writes. “Both stakeholders are engaged and at the table, working together for better medical outcomes and return to work.

“This must be contrasted with trying to resolve workers’ compensation claims through application of thousands of pages of statutes, regulations, and case law that require a team of attorneys to navigate and tens of millions of taxpayer dollars to oversee and administer.”

Perhaps not unexpectedly, the success of the Texas Option has stimulated multiple recent efforts around the U.S. to emulate elements of it. However, so far in those states — notably Oklahoma and Tennessee — lawmakers have flinched at embracing what are the key elements of the Texas plan: No benefit mandate combined with unlimited negligence liability.

In Oklahoma, private employers, so long as they mirror the state’s work-comp benefit mandate, still are protected from worker lawsuits by an exclusive remedy rule. In Tennessee, proposed legislation would combine a strong benefit mandate with a more-limited negligence liability.

Still, a growing consensus on the unsatisfactory nature of workers’ compensation after even more than a century, continues to drive an increasing recognition that intelligent, responsible employers can achieve quite large savings when they are able to exit the work-comp model.

In 2010, Alison Morantz, an associate professor of law at Stanford, completed a study for the National Bureau of Economic Research on the experience of large multistate firms that, in Texas, took the Option. Her research, funded by the National Science Foundation, found that 94 percent of respondents deemed the program a success, and that 86 percent cited as a positive surprise the magnitude of cost savings — which averaged over 50 percent.

Minick expects appreciation to grow, nationally, for what Texas has accomplished by preserving employer property rights and worker lawsuit rights. However, he also does not underestimate the resistance to change that will be posed by what he terms the “iron triangle” of vested legislators, bureaucrats and interest groups.

“It is a network of contracts and flows of billions of dollars and resources among individuals as well as corporations, state agencies, and others,” he says.

Still, even the states through which those billions of dollars flow are experiencing the high financial costs of the work-comp system. Eventually, always-rising budget pressures, coupled with the political unpopularity of work comp among many employees and employers may compel change.

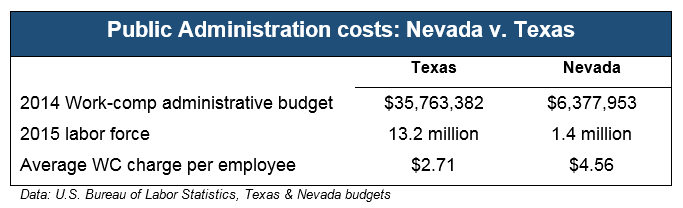

It is illuminating, for example, to compare the per-worker state administrative costs for workers’ compensation in Nevada against those in Texas.

Using 2015 Bureau of Labor Statistics numbers for the size of the respective states’ labor forces, and dividing those numbers into each state’s 2014 work-comp administration budget, yields a remarkably higher administrative charge in Nevada than Texas: $4.56 per worker in Nevada vs. $2.71 in Texas.

Two factors would seem to explain this.

First, the Texas Department of Insurance has an arguably diminished workload because of the 20 percent of Texas workers whose employers have selected the Texas Option.

Second, in Texas, the significantly freer and competitive market for insurance and administrator services and the competitive pressures have a genuine impact.

Steven Miller is the managing editor of Nevada Journal. For more visit https://nevadajournal.com or http://npri.org.

For additional reading on this subject:

Options to Workers Compensation – Public Policy Analysis,

by Bill Minick, JD, BBA, LLM

Workers’ Compensation Opt-Out: Can Privatization Work?,

by Peter Rousmaniere and Jack Roberts

Opting Out of Workers’ Compensation in Texas: A Survey of Large, Multistate Nonsubscribers,

by Alison Morantz, Ph.D.