One of the most startling revelations about how Clark County School District had been treating — or mistreating — special-needs families surfaced in 2001.

That was when a four-year-old lawsuit — accusing CCSD of denying appropriate education to a child years earlier — was finally decided by the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

The case would set an important legal precedent.

The case would set an important legal precedent.

By 2001, the girl at the center of the litigation — called “Amanda J.,” in the lawsuit — was 10 years old.

What was at issue, however, was what CCSD should have told her parents six years before.

Born in Las Vegas in 1991, Amanda at two years old had been found by a psychologist to be “moderately low” in communication and daily living skills, and recommended for the District’s early childhood program.

In March 1995, her parents had brought her to CCSD to be evaluated for special-ed placement. She was evaluated by district psychologist Mark Kenney and district speech pathologist Christy Zuckerman.

Kenney’s written report indicated that Amanda’s results on the Autism Behavior Checklist were mixed. He noted that

Her mother reported that she whirled herself for long periods of time, did not play with toys appropriately, seemed not to hear, lunged/darted about with spinning, toe-walking, etc., had severe temper tantrums, had not developed friendships, got involved with “rituals” such as lining things up, had communication problems, and had strong reactions to changes in routine [or the] environment.

Kenney observed that Amanda’s social skills were below average and concluded that Amanda was developmentally delayed. He recommended an eligibility assessment for special education, a coordinated reward / consequence system to address behavior problems, speech and language services, parental training, and further evaluation by a child psychiatrist. These recommendations were recorded in a written report that was not shared with Amanda’s mother.

Found ‘severely autistic’

The findings by speech pathologist Zuckerman were much more explicit. She found that Amanda qualified as “severely autistic” under the Childhood Autism Rating Scale, and recommended speech and language therapy, as well as additional assessments. She observed that Amanda was “non-verbal” and engaged in “random non-directed babbling,” and Zuckerman also recommended that “Specific activities should be developed and demonstrated in the classroom to stimulate social interaction and the development of communication skills.”

After the district deemed Amanda eligible for special education, the mother, prior to the initial IEP meeting, requested copies of the child’s assessment reports. The district, however, never sent them. Instead, after the initial IEP, what was sent the mother was only a two-page summary of Kenney’s observations.

Amanda attended a CCSD extended-school-year program over the summer break, and continued that fall in the district’s early-childhood special-education class.

At the end of October, however, Amanda’s family moved to northern California.

There, Dr. Michael Harris, Amanda’s uncle and a physician, noted characteristics of autism in the child. On December 15, he asked a colleague and professor of pediatrics, Dr. Robin Hansen, to evaluate Amanda.

Hansen — also Director of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics at the U.C. Davis Medical Center — issued his report on January 10, 1996.

For the first time, Amanda was officially diagnosed as autistic.

For a second opinion, Hansen referred Amanda’s parents to the Alta Regional Center. He also referred them to Families for Early Autism Treatment (FEAT) — a non-profit, volunteer-driven organization of parents and treatment professionals committed to the advocacy, education, and support of families that have children on the autism spectrum.

On February 28, 1996, Amanda’s mother had the girl evaluated by American River Speech and Hearing Associates, which recognized the severe language delay and prescribed six months of intensive speech therapy. The next day, the Alta Regional Center confirmed the diagnosis of autism.

On April 1, Amanda’s family began privately funding an in-home 15-hour-a-week intervention program. It used the discrete-trial approach that provides autistic children with the extra cues or explicit skill instructions they frequently need for learning.

Two weeks later the family requested an IEP review from the local California school district. When the IEP meeting was held, Amanda’s parents not only received updated assessments from the Alta Regional Center and American River, but they also, for the first time, saw copies of the Clark County School District’s early reports that had never been provided to them.

These were the reports which, more than a year earlier, had indicated likely autism, but had not been mentioned in the abbreviated two-page Kenney memo given to Amanda’s mother.

In October 1997, Amanda’s parents requested a due process hearing in Nevada.

At the March 1998 hearing, speech pathologist Zuckerman said she believed she’d told Amanda’s mother of the severe-autism rating, because discussing such results with parents was her general practice. Neither she nor CCSD had any documentation of any such communication, however, and Amanda’s mother denied it had happened.

After the hearing, the state Hearing Officer (HO) found that CCSD had not correctly informed Amanda’s parents of her learning disability — which meant that she had not received from CCSD the free, appropriate public education, or “FAPE,” she was entitled to under the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act.

The hearing officer’s determination would have meant that CCSD was obligated to reimburse Amanda’s parents for the cost of the 1996 California assessments indicating autism, the cost of the in-home program her parents funded from April 1, 1996 to July 1, 1996, as well as compensate Amanda for CCSD’s denial of appropriate language services during the girl’s time in the school district.

In June 1998, however, a Nevada State Review Officer (SRO) reversed the Hearing Officer’s decision. Specifically, he overturned the negative determinations that the HO had reached regarding the credibility of testimony from CCSD personnel that Amanda’s mother had, indeed, been informed of the autism findings.

The family challenged the SRO’s findings in Nevada federal court, but the court — in deference to both the factual and legal conclusions of the SRO — found the Amanda had neither been misdiagnosed nor denied a FAPE.

This was the background of the family’s further appeal to the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals.

The three-judge panel before which the case landed soon realized that it was case of first impression — that is, a case presenting an important question of legal interpretation that had never before arisen in any reported 9th Circuit case.

That question, the justices wrote, was:

[W]hat level of deference do we give to the state agencies involved in a two-tiered review process when each reaches a different result predicated on a credibility determination? In other words, to which administrative body do we accord the “due weight” standard of review for IDEA cases, established by Board of Education v. Rowley…?

Turning “to our sister circuits for guidance,” the justices then acknowledged that in most situations the final state authority — in this case, the Nevada SRO — should receive deference.

However, added the justices, they also agreed “with our colleagues in the Second, Third, Fourth, and Tenth Circuits that when an SRO overturns the credibility determinations of an HO, due weight to the decision of the SRO is not warranted.”

Which witnesses credible?

Thus, in situations where two state administrative decisions differ only with respect to the credibility of a witness, the hearing officer who personally was present at the time of the live testimony of the witnesses before him, was deemed better able to assess the credibility of the witnesses and thus was “entitled to be considered prima facie correct.”

Because the Nevada State Review Officer had stopped reviewing the case upon deciding to reject the credibility determinations of the Hearing Officer, the SRO was able to avoid addressing the matter of CCSD’s procedural violations.

The Hearing Officer, however, observed the justices, had found several violations of critical importance:

…the District did not give Amanda’s parents copies of the psychologist’s and speech pathologist’s reports finding mixed results on the autism tests, his recommendation to consider further psychiatric evaluation, or the speech and language assessment indicating “extreme autism,” all of which should have been disclosed under the IDEA.

Noted the justices:

This is a situation where the District had information in its records, which, if disclosed, would have changed the educational approach used for Amanda, increasing the amount of individualized speech therapy and possibly beginning the [discrete trial training] program much sooner. This is a particularly troubling violation, where, as here, the parents had no other source of information available to them. No one will ever know the extent to which this failure to act upon early detection of the possibility of autism has seriously impaired Amanda’s ability to fully develop the skills to receive education and to fully participate as a member of the community.

For all “the foregoing reasons,” concluded the justices, “we reverse the decision of the district court and remand,” instructing the district court to reinstate the decision of the Hearing Officer.

After the panel’s ruling, CCSD and the State of Nevada appealed the three-justice panel’s decision to the full panel of the 9th Circuit. The full panel, however, then issued a ruling, which noted that it had refused to hear the appeal and instead affirmed the ruling.

In the years following the conclusion of the Amanda J. case before the 9th Circuit, it appears that CCSD may have decided that a different strategy would henceforth be less costly to the district’s public reputation.

Ostensibly, this newer strategy would be more akin to the one identified at the start of Part Three of this series by LAUSD’s court-appointed Independent Monitor, David Rostetter. In other words: to not devote district financial resources to correcting violations of federal law until compelled to by parental lawsuits.

The calculation appears to be that this route, while costly, is still less expensive than would be required by full compliance with all the provisions of federal disability statutes. Systemic district reforms, therefore, appear to never be part of the individual-case settlements. Instead, only financial compensation for the individual child and possibly his or her guardians appear to have been on the various negotiation tables.

Virtually all of the special-needs lawsuits brought against CCSD in federal district court since the Amanda J. case appear to conform to this pattern, Nevada Journal has found.

Moreover, the court documents in these cases strongly suggest that — once attorneys for parents succeed in clearing away the many legal obstacles and opposing-counsel tactics that can prevent a jury trial — CCSD regularly opts to begin financial settlement talks, rather than risk any expensive verdicts from outraged juries.

Recurring physical abuse

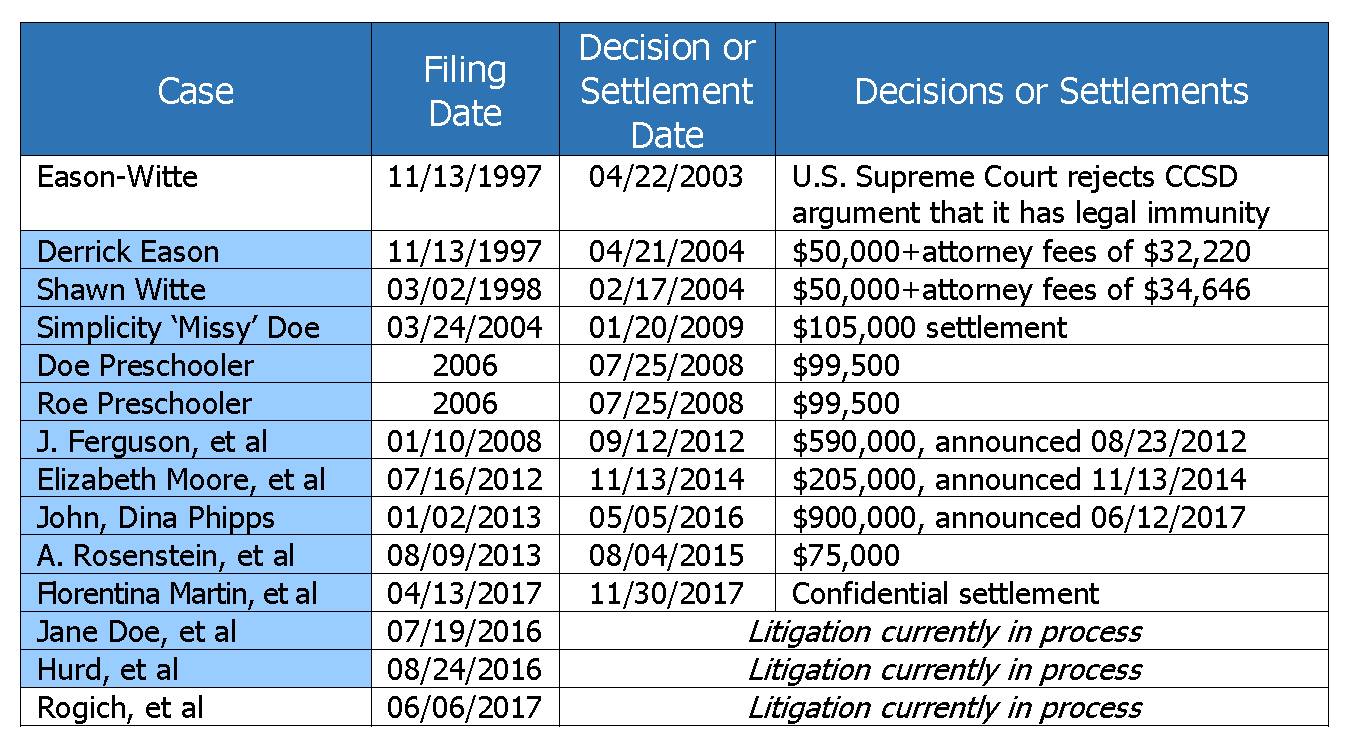

The following special-needs lawsuits — virtually all alleging physical abuse by CCSD staff — have moved or currently are moving through Nevada federal district court:

In every case but the last the complaints filed in these lawsuits allege repeated physical abuse — sometimes grossly violent — of special-needs children by certain teachers or assistants on CCSD staff.

That pattern would seem to suggest that CCSD may regularly employ individuals in its special-education division who lack the psychological maturity or professional training required to meet the real challenges that children’s disabilities sometimes demand.

Additional evidence for such a hiring pattern may have existed within an analysis that a respected national research organization provided to the Nevada legislature in 2012.

The American Institutes for Research (AIR) had been asked by lawmakers to evaluate different ways Nevada might improve “the equity by which funds are distributed to districts serving students” statewide.

While recommending that Nevada shift to a per-pupil, weighted-funding model for allocation of funds, the team of academics under contract to AIR also noted what appeared to have been a significant anomaly in the state’s historical compensation of special-education teachers.

Nevada had for years attempted to finance its special-education needs through a “unit-based” funding system, in which each of the 17 county-wide districts in the state was assigned a specific number of units.

The AIR consultants, however, found significant confusion within the state bureaucracy itself regarding how the unit-based funding approach was supposed to work.

That confusion showed up in certain incoherencies in the state’s unit-funding regime:

- The total number of students used by the state to qualify a district for a single “unit” of funding varied from 43 in Pershing County to 162 in Clark, and

- The number of students with disabilities per‐special education unit varied greatly across the state, ranging from a low of 5 students in Lincoln County to a high of 19 in Lyon County.

What may be most relevant to the quality of special-education hires in the state, however, is that the value of a special-ed “unit” for the current school year at the time (2012-13) was $39,768 — a sum that was supposed to reflect the average salary and benefits cost of a special-ed teacher.

However, wrote the AIR team:

Given that that the average compensation of a licensed teacher in the state of Nevada is $57,312… a unit value of $39,768 represents a significant shortfall of revenue, even if the number of units assigned represents some sort of equitable distribution of services or funds.

On top of that, AIR noted, Nevada’s unit approach “provide[d] no support for other licensed non‐teaching personnel who might provide services to students with disabilities, much less any support for instructional aides or non‐ personnel resources (e.g., specialized instructional materials, supplies, or technology) that might be necessary to serve students with disabilities. The special education unit as Nevada appears to use it has, at best, a vague link to the nature of the services received by any given student with a disability.”

The AIR special-ed analysis concluded with an indictment of the lack of equity in Nevada’s unit approach:

Regardless of how the number of units is determined, the current method reveals an extremely disproportionate distribution of special education units between districts based on the number of students with disabilities per allotted unit.

In 2017, the Nevada Legislature finally ended the state’s unit-funding system and replaced it with Senate Bill 178, which was represented as transitioning the state into per-pupil weighted student funding. Signed into law by Gov. Brian Sandoval, the bill primarily increased weights for students who were English-language learners, performing below certain levels of proficiency, or eligible for free or reduced-price lunches.

A provision of the bill appropriated $250,000 for hiring of independent consultants to update the AIR report and make further recommendations to lawmakers.

While true weighted student funding is an important step toward the empowerment of local school administrators, it does not address the fundamental special-ed dilemma in which Nevada school administrators — like their colleagues nationwide — have always been placed.

In Part Six, Nevada Journal turns to that subject.

Earlier in the series:

Part 1: Supremes’ decision on special-ed sets higher standards for care

Called ‘a recipe for financial disaster’ by unhappy

public-schools groups

Part 2: New, higher special-ed costs looming for State of Nevada

9th Circuit signals lack of patience with ploys

school districts have used to suppress costs

Part 3: School systems have circumvented federal special-ed law for decades

Los Angeles, Texas, New York exemplify noncompliance styles

Part 4: CCSD asked for special-ed audit then attempted to hide results

Revealed: Records tampering, state and

federal law violations, illegal IEP changes

——————

Steven Miller is managing editor of Nevada Journal and senior vice president at the Nevada Policy Research Institute.

——————