To help homeowners who couldn’t keep current with their mortgages, Nevada legislators in 2009 and 2011 changed state laws to make foreclosures more difficult for banks and other lenders.

Given all the headlines about “robo-signing” and other mortgage-industry improprieties, passage of the legislation was easy.

And when industry representatives advised caution — that the legislation could easily delay Nevada’s exit from its economic depression — sponsors of the bills, more than once, became indignant.

The new laws, the lawmakers insisted, were simply a matter of fairness — of justice.

“This bill is not about recovery,” lectured Assembly Majority Leader Marcus Conklin, the main sponsor of the often-punitive AB 284. “This is about justice, plain and simple.

“If the recovery of the housing market is more important to you than basic human justice associated with the ownership of a house,” he told other lawmakers, “then by all means vote no on this bill. I can live with that.”

Today, that question of justice and fairness has arisen again — but coming from a different angle.

Specifically: How fair were legislators to most Nevadans? To the overwhelming majority of responsible homeowners who kept up their payments — or only purchased dwellings within their means in the first place?

For those individuals, new data suggests, the changes state legislators wrote into law have been financially damaging — reducing the value of their homes even more than otherwise would be the case.

Total cost to Nevada homeowners could easily be in the billions.

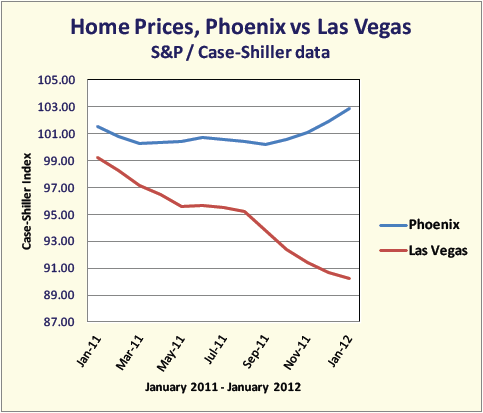

The evidence supporting such conjecture is located some 300 miles to the southeast, in Phoenix. There, in contrast to Vegas, home prices are heading dramatically upward.

While Southern Nevada residential prices, all last year and through this January, continued to decline, prices in Phoenix over the same period have instead rebounded vigorously — and much more so than anywhere else in the country.

While Southern Nevada residential prices, all last year and through this January, continued to decline, prices in Phoenix over the same period have instead rebounded vigorously — and much more so than anywhere else in the country.

The remarkable turnaround in Phoenix real-estate prices caught The Wall Street Journal’s attention on March 13. “Rise in Phoenix Housing Shows Path for Other Cities,” said the headline.

Although Phoenix was one of the hardest-hit housing markets in the country, “real-estate economists across the country,” said the Journal, are now studying the area’s “early but surprisingly broad” rebound.

“Phoenix has found a viable formula,” wrote Journal housing reporter Nick Timiraos. Part of that formula, he noted, is the ease with which banks in Arizona can take properties back from defaulting homeowners and put those properties up for sale.

Not only is that contrary to the rules in many states, where court approval is required, but it is now an important difference between Nevada and Arizona.

Both states were non-judicial foreclosure states until 2009, when Nevada legislators passed AB 149, a law that allowed defaulting borrowers to compel their lenders to participate in court-structured mediations.

Then, two years later, Silver State legislators added on AB 284, which gave defaulting borrowers even more leverage vis-à-vis the firms that had lent them money.

The new law — subsequently signed by Gov. Brian Sandoval — made lenders and mortgage servicers subject to criminal prosecution.

They are now liable to be charged with a category C felony if, in their filing of the numerous new documents the law requires, a document contains what some government prosecutor might choose to see as a “false representation concerning title.”

The mandatory sentence set by statute for such a felony is imprisonment in the state prison for least one year and fines of up to $10,000.

AB 284 also, in the view of critics, gave virtual hunting licenses to lawyers representing defaulting borrowers. It did this by placing the equivalent of bounties on any lender’s failure to disclose every prior known beneficiary of the deed of trust in a notarized affidavit. Any such mistake by a lender is, to a borrower’s lawyer, worth the greater of $5,000 or treble the amount of actual damages, plus “reasonable” attorneys’ fees and costs.

Nevada Banking Association President Bill Uffelman told Nevada Journal that, “The homeowner who hasn’t paid their mortgage in a year, two years, whatever,” now “has an ability to sue you for civil damages for foreclosing and having what are deemed to be improper documents.”

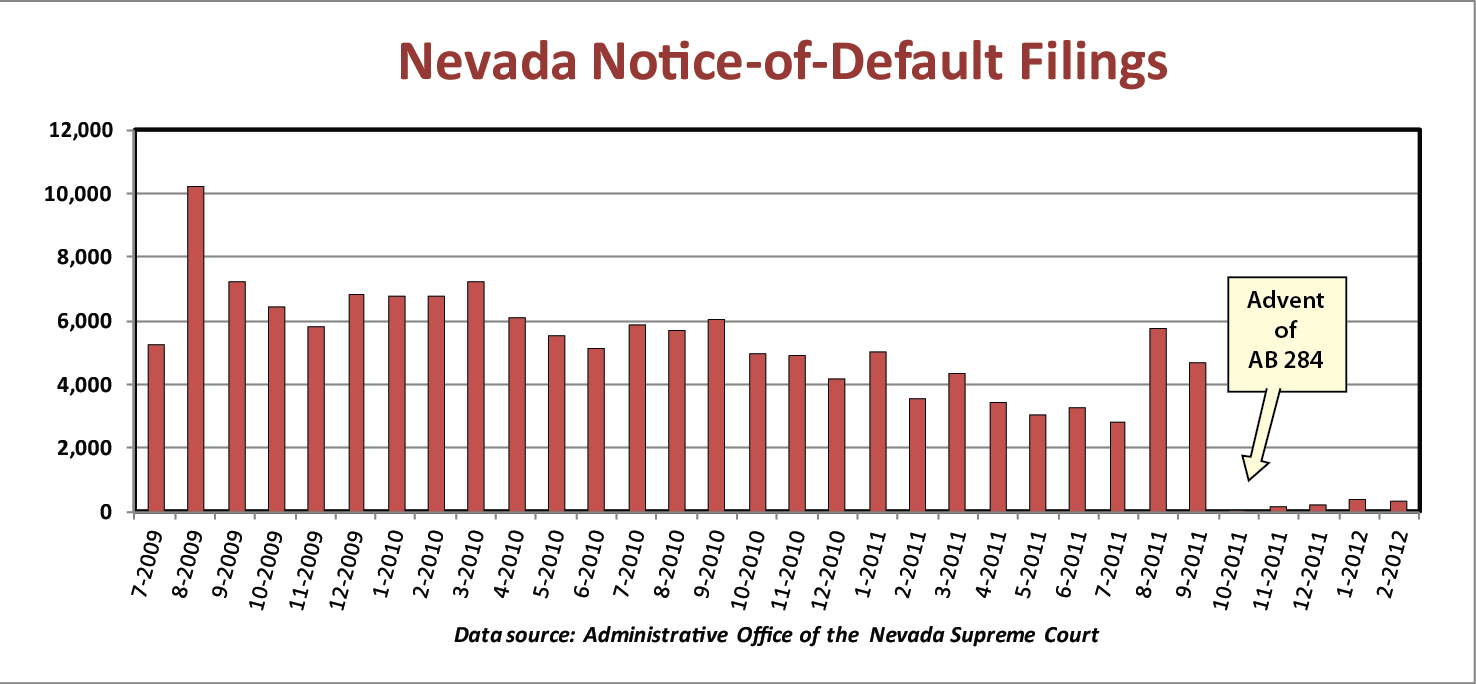

That’s the reason, he says, why lenders’ filing of notices of default — a necessary step before a bank can reclaim a house — came to a screeching halt in October, when AB 284 took effect.

Attorney Tisha Black-Chernine, who testified in behalf of AB 284 during the 2011 Legislature and whose firm is under contract to the office of Attorney General Catherine Cortez Masto, argues that AB 284 shouldn’t be blamed for the statewide drop in market-clearing foreclosures.

Figures from the state foreclosure-mediation program, however, show that filings of notices of default averaged 5,431 per month from July 2009 through September 2011, but have averaged only 211 per month since then.

In Phoenix, however, wrote the Wall Street Journal, the “local economy is on the upswing with several big employers like Amazon.com Inc. and Intel Corp. hiring again, which is further increasing demand for housing. And the region is benefiting from a surge of buyers from Canada who are using their favorable exchange rate to scoop up bargains in the desert.”

When those words were written, Case-Shiller numbers showed Phoenix home prices had jumped 0.79 percent between November and December. Since then, January’s numbers became available, showing the next month-over-month figures up another 0.91 percent.

Dennis Smith, of the Las Vegas firm Home Builders Research, believes the Wall Street Journal analysis of Arizona’s market turnaround “makes sense.”

He cautions that, in real estate, “you never say always or never or everything and nothing,” but Smith does agree that because banks in Arizona “haven’t had to deal with government intervention” of the severity of AB 284, “they’re going to put more houses on the market,” giving “investors and homeowners more to choose from.”

Paradoxically, Smith expects prices even in Las Vegas to pick up in the short term — due, ironically, to AB 284. “The bottom line is: Inventory is down, and a lot of that is due to AB 284, because the banks have closed off the notices of default.”

That improvement, however, is just “short-term,” he said. “We will improve, but we will improve much slower.”

A check of the Arizona Legislature website found that not a single piece of legislation mandating Nevada-style home-foreclosure mediation even got out of committee.

And Jeffrey Katner, housing-law manager for Community Legal Services of Arizona, confirmed for Nevada Journal that Arizona’s state legislature has repeatedly declined to pass anything comparable to either AB 149 or AB 284.

So why didn’t Arizona lawmakers behave like lawmakers in Nevada?

Differences in party philosophy appear a big part of the answer. Both chambers of Nevada’s legislature were under liberal Democratic majorities and leadership, in both 2009 and 2011. In Arizona during that time, both chambers were under Republican control.

Thus, while Arizona Democrats put together seven bills and christened the package “The Foreclosure Rescue for Arizona Act,” the Republican leadership granted a hearing to only one of the bills, according to The Arizona Republic.

Another part of the answer, however, would appear to be that Arizona, as a statewide community, has simply maintained the American West’s longstanding libertarian traditions more rigorously than has the Silver State.

In Nevada’s legislature, after all, Republicans went along with Democratic majorities and supported both AB 149 and AB 284. And both bills were also signed into law by Republican governors.

Indeed, the kind of restraint that Arizona lawmakers showed — the willingness to simply allow housing markets to go ahead and clear — appears to be increasingly rare in America today.

Alfred Pollard, general counsel to the Federal Housing Finance Agency, noted that change earlier this month. He warned that the country is seeing too “many state laws that stretch out the period for legitimate foreclosures … [and] result in no added benefit for the homeowner and produce harm to the housing finance system and to neighborhoods.”

Pollard was testifying before a Brooklyn, N.Y., hearing conducted by the U. S. House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. The subject of the hearing: U.S. housing markets’ failure to recover.

Pollard noted that the authors of a recent study by National Bureau of Economic Research “found that the result of many of the laws aimed to protect borrowers from foreclosure was delay in, but not prevention of, foreclosures. The delays contribute to an overhang in the market without borrowers finding relief during these excessive delay periods. Many borrowers neither cure their deficiency nor gain relief, but simply remain in delinquency for greater lengths of time.”

Ultimately, state schemes “that increase costs, create new liabilities for mortgagees and delay foreclosures where most borrowers are unable to cure do not benefit the majority of homeowners,” said Pollard.

Moreover, he argued, many of the state schemes aren’t even needed: “At the same time, should a borrower be treated improperly, the law has always provided protection for them for fraud or deceptive practices.

“Adding new charges before and during foreclosures, new procedures that fuel delays and otherwise encumber foreclosures in the long run will only increase costs for everyone.”

Steven Miller is the managing editor of Nevada Journal, a publication of the Nevada Policy Research Institute. For more in-depth reporting, visit https://nevadajournal.com/ and http://npri.org/.

Read more: